Slave to the Game

Online Gaming Community

ALL WORLD WARS

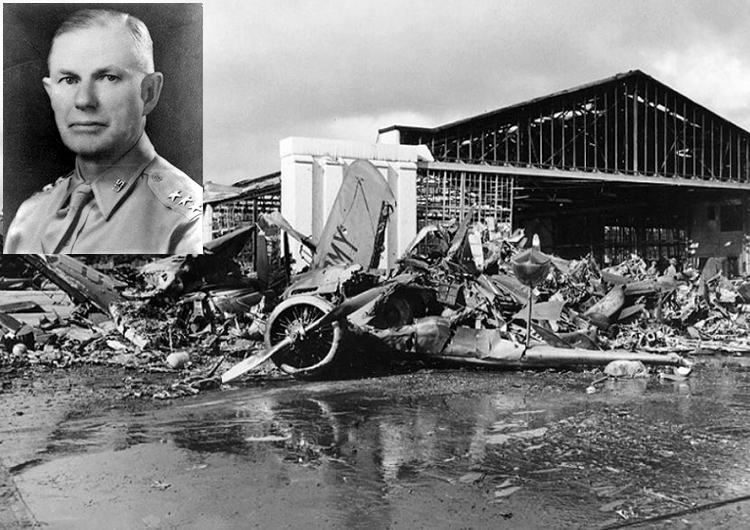

LIEUTENAT GENERAL WALTER C. SHORT - WAS HE THE ARMY'S SCAPEGOAT FOR A DISASTER?

by David L. Richey

Wheeler Airfield after Japanese Attack on Pearl Harbour, December 7, 1941

Summary

During the past years the fascinating circum¬stances leading up to the Pearl Harbor disaster have been studied in depth. This study focuses on one of the primary actors during the "Day of Infamy," Lieutenant General Walter C. Short, Commander of the Hawaiian Department and senior Army officer in Hawaii at the time of the successful surprise attack. As a result of the overwhelming success of the Japanese on 7 December 1941, General Short was relieved of his duties and forced to retire from active duty under the threat of courts martial. The purpose of this paper is to determine if General Short was unfairly held responsible for the Army's failure at Pearl Harbor as charged by the Roosevelt Administration in December 1941 and confirmed by the Roberts Commission in January 1942. The author accomplishes this task by carefully reviewing General Short's role and the roles that the other key actors played in the complex events leading up to one of America's most devastating military defeats. Through this systematic process the reader is able to better comprehend the level of General Short's responsibility in the tragedy and thus determine if he was, in fact, the Army's scapegoat for the disaster.

Lieutenant General Walter C. Short-Was He The Army's Scapegoat For a Disaster?

Over the last half century, the circumstances leading up to the successful Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor have been studied in great detail by many civilian and military scholars. And well it should be, for in one hour and forty-five minutes, 8 battleships, 3 light cruisers, 3 destroyers, and 4 other American Navy vessels, as well as the vast majority of the Hawaiian based Army and Navy aircraft, were destroyed or severely damaged.[1] Essentially, the U.S. Pacific Fleet and the largest U.S. installation outside of the continental United States were rendered combat ineffective at a cost of only 29 Japanese aircraft, 5 midget submarines, and 1 fleet submarine.[2]

Who was responsible for one of America's most decisive military defeats? Despite the efforts of a congressional committee, Army and Navy investigations, and numerous historians, it is still difficult to affix responsibility for this exceedingly complicated and controversial moment in American history. Although it may be difficult, if not impossible, to point a finger at any one event or person and say, "That is the reason the attack succeeded," the U.S. Army did, in essence, just that when the Army's senior leadership relieved Lieutenant General Walter C. Short of his duties as Commander of the Hawaiian Department less than two weeks after the attack, ultimately forcing him to retire from the service under the threat of courts martial.

In retrospect, was General Short totally responsible for the U.S. Army’s failure at Pearl Harbor as charged by the Roosevelt Administration and confirmed by the Roberts Commission? Was General Short derelict in his duties or did he demonstrate poor judgment? Did the dar Department provide General Short sufficient intelligence and adequate command guidance? These are just some of the many questions that will be analyzed to determine if General Short's relief and subsequent forced retirement was an appropriate response to his conduct, or was he, in fact, the Army's scapegoat for the disaster.

The first review of the Pearl Harbor incident was initiated by President Franklin D. Roosevelt. The President and his civilian and military advisors had expected war, but they were as surprised as were the Hawaiian commanders when the war began in Hawaii. To determine precisely what happened and why, Roosevelt sent his Secretary of Navy, Frank Knox, to Hawaii. Secretary Knox arrived on 11 December and departed for Washington the next day. in his report submitted to the President on 14 December, Secretary Knox clearly articulated the position of the Hawaiian commanders prior to 7 December 1941:[3]

There was no attempt by either Admiral Kimmel or General Short to alibi the lack of a state of readiness for the air attack. Both admitted they did not expect it, and had taken no adequate measures to meet one if it came. Both Kimmel and Short regarded an air attack as extremely unlikely because of the great distance which the Japs would have to travel to make the attack and the consequent exposure of such a task force to the superior gun power of the American fleet. Neither the Army nor the Navy commander expected that an attack would be made by the Japanese while negotiations were still preceding in Washington. Both felt that if any surprise attack was attempted it would be in the Far East.[4]

As a result of the Navy Secretary's report. President Roosevelt ordered that General Short and Admiral Husband E. Kimmel, Commander in Chief, U.S. Pacific Fleet, be relieved from command at once.[5] Additionally, the Navy and War Departments were to publicly admit responsibility for failing to be prepared for the raid and to announce that the President would convene a formal inquiry to investigate the attack. That inquiry was subsequently known as the Roberts Commission. Based on the facts gathered by the Commission, the President indicated that appropriate action would be taken.[6]

On 16 December General Short and Admiral Kimmel were officially relieved of their commands by their respective service chiefs. According to Secretary of War Henry L. Stimson, General Short was relieved because of "the absence of preparedness on December 7th." Moreover, he explained, this "action avoids a situation where officials charged with the responsibility for the future security of the vital naval base would otherwise in this critical hour also be involved in the searching investigation ordered yesterday by the President."[7]

Thus, less than one year following his appointment as Commanding General, Hawaiian Department, General Short, whose command consisted of two infantry divisions, coastal artillery and air units with responsibility for protecting the Pacific Fleet as it lay at its moorings, and the coastal defense of the Hawaiian Islands, was removed from command. Short had expected to be relieved, a traditional action when a military command suffers a great loss. But, according to his G-2, Colonel Kendall J. Fielder, "I don't think Short ever expected that the U.S. Government and the U.S. Army would turn on him the way they did."[8]

After being relieved but prior to departing Hawaii, General Short was called before the Roberts Commission. Under the direction of Supreme Court Associate Justice Owen J. Roberts, the commission was empowered by the President to investigate the circumstances surrounding the catastrophe. Completing their work in little over a month, the commission results were presented to President Roosevelt on 23 January 1942. In summary, the report found both commanders derelict of duty in that they had failed to properly assess "the seriousness of the situation" based on the war warnings available to them. Furthermore, they had demonstrated "errors in judgment" by not initiating adequate precautions and coordination, two factors identified as the "effective causes" for the Japanese success.[9]

Based on the results of the Roberts Commission, General Short was forced into retirement at the rank of major general with the proviso that he was still subject to courts martial for dereliction of duty. Thus, after 39 years of honorable and distinguished service, General Short was driven in disgrace from the Army after having been identified in the minds of the public, although never brought to trial, as the Army officer primarily responsible for the Pearl Harbor disaster.[10] Understandably, his forced retirement under the threat of courts martial was a great blow to his self-esteem and no doubt contributed to the ill health he suffered after retirement.[11]

General Short took command of the Hawaiian Department and was promoted to lieutenant general on 7 February 1941, only four days after Admiral Kimmel assumed command of the Pacific Fleet. Commissioned in 1902 following his graduation from the University of Illinois, during the next 39 plus years, General Short had the typical Regular Infantry officer assignments of his generation. Early in his career he served in Texas, at the Presidio in San Francisco, in the Philippines, in Nebraska, and in Alaska. From 1912 to 1916, he was in charge of musketry training at Fort Sill, Oklahoma. Additionally, he accompanied Pershing to Mexico as a member of the 16th Infantry Regiment. During World War I he sailed to France in 1917 as a captain and organized the 1st Corps' automatic weapons school. Later, as a member of the A.E.F. General Staff, Short directed instruction for machine-gun units. He remained in Germany after the Armistice until 1919 serving as the Third Army's Assistant Chief of Staff in charge of training. From 1921 to 1937 he spent the majority of his time in staff jobs in Washington and Fort Leavenworth. In 1937 he was promoted to brigadier general and culminated his career as commander of the Hawaiian Depart¬ment.[12]

Because of his father-in-law’s health. General Short was not enthusiastic about going to Hawaii and requested a stateside assignment knowing full well that it might cost him his third star. Understandably, when the Chief of Staff of the Army, General George C. Marshall, told him that the assignment was important and that he needed him in Hawaii, Short accepted the appointment.[13] it is thought that one of the primary reasons Marshall felt he needed Short in Hawaii was because of his superb reputation throughout the Army as an outstanding trainer. In 1941 a common command problem was effectively training raw recruits entering the Army through the draft. Since Hawaii was considered America's bastion of military strength in the Pacific, effective training to develop combat ready units was especially important.[14]

In a letter to Short dated 7 February 1941, General Marshall stressed the need for close cooperation with Admiral Kimmel. Additionally, Marshall wanted Short to clarify the respective responsibilities of their air forces in the defense of the Hawaiian Islands. Admiral James 0. Richardson and Lieutenant General Charles D. Hernon, Kimmel and Short's predecessors, had made progress in overcoming traditional inter-service resistance to Army-Navy cooperation; however, much remained to be done. Immediately upon his arrival, General Short made a special effort to cultivate a personal friendship and effective working relationship with Admiral Kimmel and Rear Admiral Claude C. Bloch, Commandant of the Fourteenth Naval District with responsibility for the Navy's local defense except for on board activities. In point of fact, Bloch's command only consisted of some Marine Corps attachments and those aviation elements that could be spared from the fleet.[15]

Furthermore, in his letter to Short, General Marshall pointed out the "the fullest protection for the fleet is the rather than a major consideration" for the Army in Hawaii and he added:

My impression of the Hawaiian problem has been that if no serious harm is done us during the first six hours of known hostilities, thereafter the existing defenses would discourage an enemy against the hazard of an attack. The risk of sabotage and the risk involved in a surprise raid by air and by submarine constitute the real perils of the situation.[16]

In response to Marshall's guidance, General Short took timely steps to work out the respective responsibilities for the Army and Navy air forces. The Joint Coastal Frontier Defense Plan signed by Bloch and Short on 11 April stated that the Army would "hold Oahu against attacks by sea, land and air forces and against hostile sympathizers [i.e., fifth columnists], to support the naval forces." The Navy was tasked "to patrol the coastal zone and to control and protect shipping therein, [and] to support Army forces." The agreement required the Army to establish "inshore aerial patrol of the waters of the Oahu D.C.A. in cooperation with the Naval Inshore Patrol . . . and an aerial observation system on outlying islands, and an Aircraft Warning Service for the Hawaiian Islands." The Navy was to conduct inshore patrol, an off shore patrol and distant reconnaissance. This agreement was tested in joint exercises during 1941 and seemed to work reasonably well.[17]

Although Army-Navy cooperation had improved since Short and Kimmel assumed command/ the plan showed that inter-service prejudice still existed as evident by the fact they could not agree to establish an unified command responsible for coordinating all air force activities. As the opening statement of the agreement stipulated, "the method of coordination will be by mutual cooperation ... until and if the method of unity of command is invoked." There is good reason to believe "unity of command" would only have been achieved during a recognized emergency.[18]

In a joint paper called the Martin-Bellinger Report after Major General Frederick L. Martin and Rear Admiral Patrick N. Bellinger, Commander, Hawaiian Army Air Force, and Commander, Hawaiian Navy Patrol Aircraft, respectively, it was apparent that it would be very difficult to foresee such an emergency.[19] The report, submitted only three days prior to the signing of the Joint Coastal Frontier Defense Plan, predicted a dawn Japanese air attack on the Pacific fleet at Oahu prior to a formal declaration of war. Furthermore, the report indicated that the best way to preclude a surprise attack was through distant air reconnaissance conducted in every direction out to three hundred miles. To accomplish this task Hawaii would require 180 B-17s. At that time, however, there were not that many В-17s in the entire United States, much less available for use in Hawaii.[20] During the summer of 1941 there were 21 B-17s and 69 Navy patrol planes on Pearl Harbor.[21] Actually, far less than 69 Navy aircraft were available for long range patrol since their priority mission was to support the fleet's preparation for war. Given such limited resources, the only viable solution was to conduct sustained long distance recon¬naissance only when intelligence sources indicated that a potential Japanese attack was imminent.[22]

General Short informed Washington of his agreements on matters of mutual interest to the Army and Navy, indicating to Marshall that he felt that all possible steps required to enable the two forces to act together with unity of command had been accomplished. Somewhat later Admiral Kimmel reported substantially the same thing to Washington, adding that there was a critical need for a great many more Army heavy bombardment planes in order to conduct long range reconnaissance in a systematic, long-term manner.[23]

On 7 December 1941, there were twelve more heavy bombers on Pearl Harbor as compared to April 1941. However, these aircraft were used primarily for training combat crews needed in the Philippines and for spare parts. The Navy, which admittedly had responsibility for long range reconnaissance, did not have adequate aircraft or crews to effectively accomplish this mission. The Army Hawaiian Air Force was responsible for providing available long range aircraft to the Navy to supplement their reconnaissance capability. But, even with Army aircraft, the Navy would not conduct meaningful, long-range reconnaissance.[24]

Specifically, on 7 December the Army could have provided the Navy with an additional six B-17s capable of long-range patrol. The Navy, however, did not request any Army aircraft. Thus, General Short was confident that the Navy was somehow meeting its reconnaissance responsibilities. He knew that the Navy had a radio traffic analysis unit that monitored the location of the Japanese fleet. He also knew that the Navy had radar equipped ships and that naval task forces were always outperforming scouting missions. But, on 7 December, Short did not know either the location and activities of the Pacific Fleet or the number of sorties and routes of naval aerial reconnaissance missions. To make matters worse, it was Short's policy not to delve into Kimmel's naval responsibilities. "As a Senior Admiral," General Short remarked, "Kimmel would have resented it if I had tried to have him report every time a ship went in or out, and as I say, our relations were such that he gave me without hesitancy any piece of information that he thought was of interest." General Marshall's instructions to develop cordial relations with the Navy had been carried out both in letter and in spirit by Short.[25] In fact, Short's burning desire to maintain effective relations with Kimmel may have caused him and his staff not to ask the Navy the necessary tough questions to properly coordinate Army-Navy defense activities.

As previously mentioned, under the Joint Coastal Frontier Defense Plan, the Army was responsible for installing an Aircraft Warning Service (AWS). On December 7th the AWS consisted of five or six mobile radar sites located on Oahu. However, only three of these sites were operational on the day of the attack.[26] The radars had the capability of detecting enemy aircraft out to a range of approximately 130 miles. The sites were operating on a training basis under the operational control of the Signal Corps. The Air Force wanted the sites to be operated on a 24-hour basis. To do so, however, was thought to be impractical due to the nonavailability of repair equipment and trained radar mechanics. Earlier, Short, who from March to August 1941 had seen a significant improvement in the range and reliability of the AWS system, wrote Admiral Kimmel that AWS was "rapidly nearing completion." Inaccurate though it was, Kimmel was left with the impression that the AWS would be completed and become a functioning part of the Intercept Command in the near term. That, of course, was not the case. On 28 November, the day after receiving a message from the War Department that stated that hostile action with Japan was possible at any moment, Short changed AWS radar sites operating hours from 0600-1130 to 0400-0700 hours daily. The rational behind the change in operating hours was because Short considered these to be "the most dangerous hours" for an air attack. Short did not, however, tell anyone why he changed the hours. Thus, radar personnel inaccurately assumed that the shift was to save wear and tear on the equipment.[27]

On the morning of 7 December the Opana radar site on Oahu, scheduled to shut down at 0700 hours, continued to operate so that an operator could receive additional training. At about 0702 hours the station picked up a flight of aircraft located 137 miles north of Oahu. This important news was reported to the AWS Information Center. The officer on duty, an inexperienced Air Corps Reserve lieutenant, thought that what the radar operators were seeing was a flight of B-17s due in from the mainland.[28] Hе may not have made this invalid assumption had the operators told him that they had 50 blips on their screen [29] or if prearranged aircraft approach corridors had been established.[30] Failure to establish approach corridors was a critical deficiency. In the end, responsibility for this failure has to rest squarely on General Short's shoulders.

Even if the AWS sites had been operating on a 24-hour basis and alert procedures been executed to perfection, the Army would have been provided with only a 45 minute warning; the Navy maybe 30 minutes.[31] Based on the alert status in which Short had placed his command, this would not have been enough time to get ammunition from the bunkers to the anti¬aircraft guns, or to get the Army Air Force armed and off the ground prior to the Japanese attack.[32] The rational behind Short's decision to place his command in such a low alert status will be discussed later.

In addition to attempting to clarify Army and Navy responsibilities and improve the capability of the AWS system, Short took aggressive steps to improve land defenses. Skillfully using salvaged material, he had constructed beach obstacles and firing emplacements on those beaches he considered to be potential landing sites.[33] не reorganized his four infantry regiments into two divisions and garrisoned several of them on the outer islands. Short improved protection to Army aircraft by constructing dispersal runways and bunkers and by building new airfields on Oahu and the other islands to reduce the friendly aircraft concentration on the main island.[34]

A valid assessment of General Short's conduct as commander of the Hawaiian Department would not be complete without taking into account the intelligence that the Hawaiian Command received from Washington prior to the attack and his response to it.

Early in 1941 Washington broke the Japanese Purple Code, which was the key to the Japanese high security communication system. The system employed sophisticated machines to accomplish enciphering and deciphering. The code was broken so completely by Washington that the mechanics of the machine were fully understood thus enabling American and British intelligence units to reproduce a number of the Purple cipher machines. The dispatches decoded by the Purple machines were called "Magic" by its recipients.[35] Magic was so important that only

a few very key individuals saw it. General Short was not one of the chosen few recipients.[36]

Eight Purple machines existed in 1941. Four were in Washington —two each for the Army and Navy. Three were in London. The last machine was sent to the Commandant of the Sixteenth Naval District in the Philippines. Pearl Harbor did not receive a machine. The distribution of the machines reflected the focus on the perceived potential threat to the United States at the highest levels of our government.[37] In 1941 our government was consumed with the war in Europe and concerned about Japanese intentions in the Far East. Most senior government officials felt that if the Japanese did attack U.S. forces in the Pacific, it would be in the Philippines, not the Hawaiian fortress.[38]

Since a Purple machine was not provided to the Hawaiian intelligence units, the decoding of Japanese diplomatic traffic was impossible, necessitating that the Hawaiian Department forward intercepted diplomatic traffic to the War Department for decoding. General Short did obtain sporadic intelligence information from Admiral Kimmel and other Hawaiian Department intelligence units. His organic intelligence units also provided information on Japanese radio traffic, such as the volume of messages, and the direction finder bearings to transmitting units. Such information, however, is of little value without further information to supplement it, enabling the formulation of sound intelligence. In this regard, the War Department had the vital responsibility of providing General Short with accurate and timely intelligence so that he could make sound command decisions.

Prior to late September 1941, the Japanese diplomatic reports on movements of U.S. naval units in the Hawaiian area were routine and served merely to keep Tokyo informed of the strength and composition of the U.S. naval forces in Hawaiian waters. On the 26th of September, Tokyo sent its Consulate in Hawaii a dispatch dividing the waters of Pearl Harbor into five sub-areas. The message further stated that Tokyo wanted information on U.S. warships and aircraft carriers docked and at anchor, using the sub-areas to depict the location of the ships. On 15 November, Tokyo ordered the Japanese Consulate to step up the frequency of the reports on Pearl Harbor to two a week. On the 29th of November, Tokyo sent its Hawaiian Consulate a dispatch directing that reports be forwarded to them even when no ship movement was observed. Contained in the dispatch of 29 November was the emphasis for secrecy.[39] The Japanese dispatches on U.S. naval movements were intercepted in Hawaii and relayed to Washington for decoding. However, not the slightest hint of information contained in the Japanese dispatches was transmitted back to General Short.[40]

During November 1941, the diplomatic traffic between Tokyo and Washington was heavy [41] as the Japanese sought to conduct meaningful negotiations with the United States prior to 29 November. Throughout the month of November, intercepted Japanese diplomatie traffic from Tokyo to its Washington Embassy stressed the importance of negotiations which were to be completed by 29 November. They indicated that after that date* "Things were automatically going to happen."[43] Throughout the month the attempts at negotiations by both the United States and Japan were futile. On 26 November, Secretary of State Cordell Hull handed the Japanese Ambassador an American counter proposal to a recent Japanese diplomatic effort which, in Tokyo's view, virtually terminated the negotiations.[44] However, the Tokyo government informed its Washington Embassy to maintain the appearance of continuing negotiations, indicating that surprise was an essential element of those events which were "automatically going to happen."[45] Again, not a word about the contents of the Japanese diplomatic dispatches was ever transmitted to General Short.[46]

Ultimately, the War Department's failure to provide General Short with important intelligence information during November and December 1941 contributed to the Hawaiian Department Commander's failure to appreciate the seriousness of the Japanese threat. Access to this and other important intelligence information available in Washington, coupled with the limited intelligence information that was made available to General Short prior to December 7th, may have caused him to place his command on an alert status that would have defeated or at least reduced the success of the attack.

A Japanese message of utmost importance was intercepted on 27 November 1941[47] and made available to the War Department on 1 December 1941.[48] it stated that the Japanese Consulates and Embassies within the United States, and in certain other foreign countries, were to destroy codes, code machines, ciphers, and secret correspondence as of 3 December.[49] Yet again, this extremely sensitive information was not made available to General Short.[50] Admiral Kimmel was provided this information, but he did not share it with Short because he presumed that the General had also received the information.[51]

On November 27, General Short received the following important radiogram from the War Department:

Negotiations with the Japanese appear to be terminated to all practical purposes with only the barest possibilities that the Japanese Government might come back and offer to continue. Japanese future action unpredictable, but hostile action possible at any moment. If hostilities cannot, repeat cannot be avoided the United States desires that Japan commit the first overt act. This policy should not, repeat not be construed as restricting you to a course of action that might jeopardize your defense. Prior to Japanese action you are directed to undertake such reconnaissance and other measures as you deem necessary, but these measures should be carried out so as not, repeat not, to alarm the civil population or disclose intent. Report measures taken. Limit the dissemination of this highly secret information to minimum essential officers.[52]

Because of the conflicting instructions and ambiguity, the radiogram has been named the "Do or Don't" message.[53]

Although the message was sent under General Marshall's signature, he was, in fact, away in Louisiana at the time of its release watching War Games. The message was actually drafted by Secretary of War Stimson and the Chief of War Plans, Brigadier General Leonard T. Gerow. During the drafting of the "Do or Don't" message. Secretary Stimson consulted with the Secretary of Navy, Knox; the Chief of Naval Operations, Admiral Harold R. Stark; and the Acting Chief of Staff/War Department G-2, U.S. Army Brigadier General Sherman Miles. All of the key government officials and military officers consulted recommended changes to the text. The recommended changes were then incorporated into the message, ultimately contributing to its misleading and ambiguous wording.[54]

The ambiguity of the "Do or Don't" message is made evident by such quotes from the message as, "Hostile action possible at any moment . . . Take such reconnaissance and other measures as you deem necessary," with an accompanying warning about leaving the first act to Japan and not alarming the civil population. Nowhere in the message was the action desired of the Hawaiian Department Commander clearly stated.[55] This meant that General Short, without the knowledge of critical information available in Washington, had to decide what to do on his own.

He went over the message word by word. To him it seemed "That the avoidance of war was paramount and the greatest fear of the War Department was that some international incident might occur in Hawaii and be regarded by Japan as an overt act."[56] He was also very sensitive to Washington's instructions not to alarm the local population and to the need to limit dissemination to the minimum number of essential officers. This need to limit dissemination may have caused him not to discuss its contents with his subordinate commanders. Since Marshall knew of his agreement with the Navy under which they were to conduct long distance reconnaissance in Hawaii,[57] Short thought that the message, which was also sent to the Philippines, was written primarily for MacArthur.[58]

In preparation for war, Short had developed three prearranged states of alert. Number 1 was an alert against sabotage. Number 2 was the same as number 1 with the addition of defense against air, surface and submarine attack. Number 3 was an all out alert with all personnel moving to their battle stations to repel a possible landing. Placing the command on alert status 2 or 3 would arouse public attention and require informing several officers about the warning from Washington. Still, during 1941, Short had conducted several alert exercises that caused his soldiers to move to their battle stations. Therefore, was it logical for Short to think that one more full scale alert exercise would raise undue civilian suspicion or be interpreted by the Japanese as an overt act of war. Probably not. Perhaps key to understanding Short's decision is the fact that he ultimately concluded that a Japanese air attack was highly unlikely and that the alert status should be balanced with training requirements such as training B-17 crews needed in the Philippines. Moreover, Short's false belief that Washington would advise him if there was going to be an all-out attack on Hawaii, led him to decide to put his command only on alert against sabotage.[59]

Short's decision to place the Hawaiian defenders on alert status number 1 helped the Japanese achieve one of their vital pre-mission objectives — to destroy the American air forces on the ground thus preventing them from disrupting their attack on the Pacific Fleet or counter-attacking the Japanese task force. Short's alert against sabotage meant that Army aircraft were parked unarmed in the open, wingtip to wingtip. Such positioning was designed to counter fifth column dangers. Short thought that it would take 30 minutes' warning to get the aircraft dispersed. Unfortunately, he did not take into consideration the additional time required to arm the aircraft and to get them airborne. As we know, there was no advanced warning. The U.S. Army Air Force in Hawaii made perfect targets for the Japanese bombers and fighters. Short's decision to go on alert merely against sabotage, coupled with Kimmel's failure to conduct distant reconnaissance with his limited aircraft resources, virtually guaranteed a successful Japanese attack.[60]

On 28 November, General Short replied to the War Department on the "Do or Don't" message as follows: "Received your radio message 472, November 27: Report department alerted to prevent sabotage. Liaison with the Navy."[61] The Commander of the Hawaiian Department received no reply from Washington and interpreted the silence to mean approval of his sabotage alert status.[62]

In Washington, General Short's reply went through Gerow to Marshall as did MacArthur's reply to the "Do or Don't" message. Marshall initiated MacArthur's reply which stated that the Army, in conjunction with the Navy, would begin conducting extended air reconnaissance and that everything was in readiness to conduct a successful defense. Short's reply, however, was not initialed by Marshall. Later, before a congressional committee, Marshall stated that he could not recall having seen Short's alert status, but did acknowledge, "That was my opportunity to intervene, and I did not do it." Not only did Marshall miss the opportunity, but so did Stimson who did see the message and failed to voice any dissatisfaction.[63]

Admiral Kimmel received a similar, but more strongly worded message from the Navy Department on 27 November. Kimmel had a paraphrased copy of that message sent to Short the same day. The message started with, "This dispatch is to be considered a war warning." Short interpreted the sentence as "no more than saying Japan was going to attack some place." The rest of the Navy message, so similar to the one he just received, had little effect on Short. In general, the same can be said for the effect the message had on Kimmel, for it did not convince him to initiate aggressive long distance aerial reconnaissance activity.[64]

General Short received two additional messages after the receipt of the "Do or Don't" message, both of which supported his conclusion that he had initiated the kind of alert Washington wanted. Brigadier General Miles, War Department G-2, sent a message to General Short's intelligence section on the evening of the 27th of November which read: "Japanese negotiations have come to practical stalemate. Hostilities may ensue. Subversive activities may be expected. Inform Commanding General and the Chief of Staff only."[65]

Meanwhile, General Henry H. Arnold, Chief of the Air Corps, sent General Martin, Chief of Army Air Forces in Hawaii, a message on 28 November relating entirely to sabotage and subversive activities similar to the message by General Miles. The message instructed General Martin to report his actions taken in response to the 28 November message prior to December 5. General Short and General Martin sent a detailed report to Washington on December 4, informing the War Department of the actions taken by the Hawaiian Command against sabotage and subversion.[66] An excerpt of the report shows that it was written in a clear, concise manner allowing no room for misinterpretation by the reader: "This entire department is now operating and will continue to operate under an alert for prevention of sabotage."[67]

Again, no reply was forthcoming from Washington. Surely if someone in Washington did not desire the Hawaiian Department to operate under an alert for sabotage or did not understand what this alert status meant, they would have asked General Short for a clarification — but no one did.

During the critical period just prior to the attack, Short and Kimmel failed to share important information and coordinate their activities. Between 1 and 3 December they met daily to discuss the Army's relief of Midway, a topic on which they did not agree. During these meetings they discussed the war warning messages, but despite these daily meetings, Short did not know if the Navy was conducting long range reconnaissance, and Kimmel did not clearly understand the Army's alert status.[68]

The last "gift" from Magic prior to Pearl Harbor was received on 6 and 7 December. The first thirteen parts of a fourteen-part message from Tokyo to Japan's Ambassador in Washington consisted of Tokyo's vehement rejection of what the U.S. termed a proposal for Japan to pull its troops out of China and Indochina. The U.S. would reciprocate by lifting economic sanctions imposed on Japan. Understandably, Japan considered the proposal an ultimatum. Except for General Marshall, distribution of the message to all high officials authorized to see Magic was completed before midnight on 6 December. When the President read it he is said to have remarked, "This means war." Still, no action was taken in Washington to inform commands in the field that war might be imminent.[69]

Early the next morning the final part of the message arrived. It said:

Will the Ambassador please submit to the U.S. Government (if possible the Secretary of State) our reply to the United States at 1:00 PM on the 7th, your time.

When Colonel Rufus S. Bratton, the U.S. Army officer responsible for distributing Magic, received the fourteenth part of the text at 9:00 a.m., he quickly understood the implications. One PM Washington time was dawn in Hawaii and early morning in the Far East. He immediately tried to telephone the Army Chief of Staff. Marshall, unaware of the previous evening's signal, was out for his usual horseback ride. By the time he reached his office, the President, the Secretaries of State, Navy and War; the Chiefs of Army and Navy Intelligence, the Chiefs of Army and Navy War Plans Division, and the Chief of Naval Operations, had reviewed and discussed the intercept. But, it was not until Marshall finally arrived in his office at 11:25 a.m. that action was taken to send a warning to Pearl Harbor.[70]

The final message from Washington to Hawaii was drafted by General Marshall and ready for dispatch one hour and twenty seven minutes prior to the Japanese attack.[71] The message read:[72] Japanese are presenting at 1:00 PM EST today what amounts to an ultimatum. Also, they are under orders to destroy their code machines immediately. Just what significance the hour set may have we do not know, be on alert accordingly. Inform naval authorities of this communication.[73]

Since the Army was having trouble maintaining communications between Hawaii and Washington, the decision was made to send the message by RCA commercial radio. Classified routine and lacking any urgent markings further slowed the handling of the message. Accordingly, the warning was not received by General Short until seven hours after the attack began.[74]

General Marshall had on his desk a telephone scrambler which could have been used to inform General Short of the situation within minutes. The Chief of Staff later stated that he did not use the device because he did not feel it was secure. He also testified that if he had used the phone, he would have called the Philippines and Panama prior to Short in Hawaii. Interestingly, the same scrambler telephone system was used throughout the war for conversation between Roosevelt and Churchill without any apparent compromise. General Marshall also had at his disposal powerful Navy and Federal Bureau of Investigation radio transmitters. Admiral Stark, who was with General Marshall when he drafted the last minute warning, asked the Chief of Staff if he would like to use the Navy transmitter. General Marshall replied "that he believed he could get it through in an expeditious manner." Unfortunately, the message was not handled in an expeditious manner. Even if it had been, so little time remained before the attack that it is doubtful that it would have significantly improved chances of defeating the Japanese.[75]

A number of commissions and boards were conducted to decide what led to the disaster at Pearl Harbor. These included the previously mentioned Roberts Commission, War and Navy Department Investigations« and a Congressional Enquiry. Even after all of these reviews of the disaster were completed« it was not until the war ended and it became common knowledge that President Roosevelt had had access to Magic that the revisionist theory began to appear in print. In general, the revisionists argued that based on Roosevelt's access to Purple intelligence, he had to have known of the impending attack on Hawaii and had deliberately refused to inform the field commands in the hope that the Japanese attack would bring the U.S. into the war.[76] Many books have been written speculating on Roosevelt's responsibility for the success of the attack. Not surprisingly, this interpretation was strongly supported by the extreme right for political reasons.

However, reliable historians do not support this theory. Although the intelligence available should have indicated to the Roosevelt Administration that an attack was imminent, according to William Friedman, Technical Director of the Signal Intelligence Service in 1941 and the man credited with breaking Purple, "There were no messages which can be said to have disclosed exactly where and when the attack would be made." [77]

Unquestionably, the decision makers in Washington had an impressive amount of information on the Japanese. But, as Wohlstetter says in her book, Pearl Harbor, the signals that may be characterized with 20-20 hindsight as absolute war warnings of a pending surprise attack were, in November and December 1941, ambiguous indicators leading nowhere. In late 1941 the U.S. was preoccupied with the war in Europe. Signals from the Far East were also arriving in Washington. This intelligence seemed to depict a Japanese danger to Soviet Russia or Dutch and British Pacific targets. Military and civilian authorities in Washington and Pearl Harbor were lost in the belief that the Pacific Fleet acted as an offensive deterrent force rather than a target. In short, they under¬estimated Japanese capabilities and intentions, developing, in the words of Admiral King, an "unwarranted feeling of immunity of attack." Based on this fundamental premise, Washington was unable to discern from the "intelligence noise” that Pearl Harbor was the primary target.[78]

If Washington could not be expected to anticipate the attack on Pearl Harbor, why should Short, who had access to far less pertinent intelligence information, be expected to have been prepared for an impending attack? As the commander of the Hawaiian Department, Short had the traditional respon¬sibilities of all U.S. Army commanders. That is, he was responsible for everything his unit did or failed to do. He had the authority and the responsibility to put the Hawaiian Department on full alert if he felt the threat warranted it. As a senior leader, he should not have waited for Washington to tell him what to do. Although the information available to Short did not specifically state that Pearl Harbor would be attacked, he did possess sufficient intelligence based on the Navy Department's "War Warning" message, the War Department's less alarming "hostile action possible" message» and the message from the War Département 6-2, and the Chief of Staff of the Air Corps, to place his unit on a higher state of alert. Unfortunately, he did not. He compounded this critical mistake by failing to coordinate with Kimmel, to verify that the Navy was conducting long range aerial reconnaissance, or to determine the activities of the Pacific Fleet.

Short's primary mission in Hawaii was to protect the Pacific Fleet in its mooring at Pearl Harbor. But, as Represen¬tative Hamilton Fish of New York said concerning the status of Short's Hawaiian Department readiness, "We were in a state of preparedness instead of a state of alertness." Short was so preoccupied with training issues and the threat of sabotage, that he failed to execute his primary mission — to protect the fleet.[79] Not unlike the vast majority of senior U.S. Government officials and military officers, Short was sure that Pearl Harbor was an improbable Japanese target. It was this belief that impacted constantly on the key decisions he made just prior to the attack.

Short's relief was, in a military sense, the correct punishment, and was publicly necessary in order to fix the blame for the catastrophe so that the nation could put the disaster behind it and focus on Japan's defeat. Undoubtedly, Short made enough serious mistakes to warrant his relief. But, was it warranted and necessary to force Short into retirement and threaten him with a courts martial? Probably not, since it appears that public sentiment was satisfied merely with his relief. The action taken against Short seems even more unfair when compared to what happened to other field commanders who were also unprepared for the surprise attacks of 7 December. For example. General MacArthur was not relieved or forced into retirement for failing to have his Philippine Command fully prepared for the Japanese attack. And his forces were not attacked until 9 or 10 hours after the Pacific Fleet lay on the bottom of Pearl Harbor.[80]

General Short had too much to contribute to the war effort to be forced into retirement. A renowned trainer, his training programs in Hawaii are today recognized as having contributed in large measure to the success that the 24th and 25th Divisions enjoyed in the Pacific during World War II. The Army and the nation would have been better served by letting Short use his years of experience and expertise to train soldiers for combat. Lieutenant General Lloyd R. Fredendall, 2nd U.S. Army Corps commander during its defeat by the German African Corps at Kasserine Pass, is an excellent example of an unsuccessful field commander who was subsequently given a training command so that the nation could benefit from his unique and much needed qualities by training soldiers for combat.[81]

In the eyes of the public, General Short was unjustly held totally responsible for the Army's failure in the "Day of Infamy." To the overwhelming extent that Short shouldered the Army's share of the blame for the disaster and was forced into retirement, he was a scapegoat. This should not, however, be interpreted to mean that General Short was blameless. He clearly was not. Without his errors in judgment the Japanese attack would not have been as successful as it was.

Endnotes

1. Stetson Conn, Rose C. Engelman and Bryon Fairchild, U.S. Army in WWII, The Western Hemisphere, Guarding the U.S, and its Outposts, Office of the Chief of Military History, Department of the Army (Washington, D.C., 1964), p. 188.

2. Ibid.

3. Ibid., pp. 194-95.

4. Ibid.

5. Donald Grey Brownlow, The Accused - The Ordeal of Rear Admiral Husband Edward Kimmel, U.S.N. (Vantage Press, New York, NY, 1968), p. 143.

6. Martin V. Melosi, The Shadow of Pearl Harbor (Texas A&M University Press, College Station, Texas and London, England, 1977), p. 25.

7. Gordon W. Prange, At Dawn We Slept (McGraw-Hill Book Company, New York, NY, 1981), pp. 589-90.

8. Prange, p. 590.

9. Claude R. Sasso, "Scapegoats or Culprits: Kimmel and Short at Pearl Harbor," Military Review, Volume LXIII No. 12, December 1983, U.S. Army Command and General Staff College (Leavenworth, KS, December 1983), pp. 31-32.

10. Prange, p. 590.

11. Conn, Engelman and Fairchild, pp. 153-56.

12. Prange, p. 53.

13. Ibid.

14. Ibid., p. 54.

15. Conn, Engelman and Fairchild, pp. 163-65.

16. Ibid., p. 163.

17. Roberta A. Wohlstetter, Pearl Harbor, Warning and Decision (Standford University Press, Standford, CA, 1962), pp. 19-20.

18. Ibid., p. 19.

19. Conn, Engelman and Fairchild, pp. 165-66.

20. Sasso, p. 35.

21. Conn, Engelman and Fairchild, p. 167.

22. Prange, pp. 95-6.

23. Conn, Engelman and Fairchild, p. 166.

24. Ibid., pp. 166-67.

25. Wohlstetter, pp. 24-28.

26. Conn, Engelman and Fairchild, p. 186.

27. Wohlstetter, pp. 9-10.

28. Ibid., p. 11.

29. Prange, pp. 500-501.

30. Ibid., p. 730.

31. Wohlstetter, p. 12.

32. Conn, Engelman and Fairchild, pp. 195-96.

33. Sasso, p. 36.

34. Conn, Engelman and Fairchild, pp. 168-71.

35. Robert A. Theabald, The Final Secret of Pearl Harbor (Devin-Adair Company, New York, NY, 1954), pp. 32-33.

36. Prange, p. 252.

37. Ronald Clark, The Man Who Broke Purple (Little, Brown and Company, Boston, MA, and Toronto, Canada, 1977), p. 157.

38. Wohlstetter, pp. 170-82.

39. Theabald, pp. 42-47.

40. Ibid., p. 47.

41. Ibid., p. 48.

42. George Morgenstern, Pearl Harbor, The Story of the Secret War (Devin-Adair Company, New York, NY, 1947), p. 184.

43. Ibid.

44. Ibid.. p. 163.

45. Theabald, p. 59.

46. Ibid., p. 60.

47. Ibid., p. 63.

48. Han L. Trefousse, What Happened at Pearl Harbor (United Printing Services Inc., New Haven, Conn, 1958), p. 71.

49. Trefousse, p. 71.

50. Ibid.

51. Prange, p. 450.

52. Morgenstern, p. 226.

53. Ibid.

54. Ibid., pp. 226-27.

55. Trefousse, pp. 61-63.

56. Prange, p. 402.

57. Ibid., pp. 402-03.

58. Ibid., p. 404.

59. Ibid., pp. 402-04.

60. Ibid., pp. 411-13.

61. Trefousse, p. 65.

62. Theabald, p. 230.

63. Prange, p. 42.

64. Brownlow, pp. 112-13.

65. Morgenstern, p. 229.

66. Ibid., pp. 232-33.

67. Ibid., p. 233.

68. Sasso, p. 42.

69. Prange, pp. 474-75.

70. Ibid., p. 486.

71. Ibid., pp. 486-95.

72. Morgenstern, p. 238.

73. Theabald, p. 115.

74. Morgenstern, p. 238.

75. Prange, pp. 494-95.

76. Clark, pp. 170j-71.

77. Ibid.

78. Wohlstetter, pp. 387-88.

79. Prange, p. 721.

80. Wohlstetter, p. 396.

81. Martin Blumenson, Kasserine Pass (Houghton Mifflen Company, Boston, Ma., 1967), pp. 303-04.

1988