Slave to the Game

Online Gaming Community

ALL WORLD WARS

THE BRITISH

WAR BLUE BOOK

DOCUMENTS

CONCERNING

GERMAN-POLISH RELATIONS

AND THE

OUTBREAK OF HOSTILITIES BETWEEN

GREAT BRITAIN AND GERMANY

ON SEPTEMBER 3, 1939

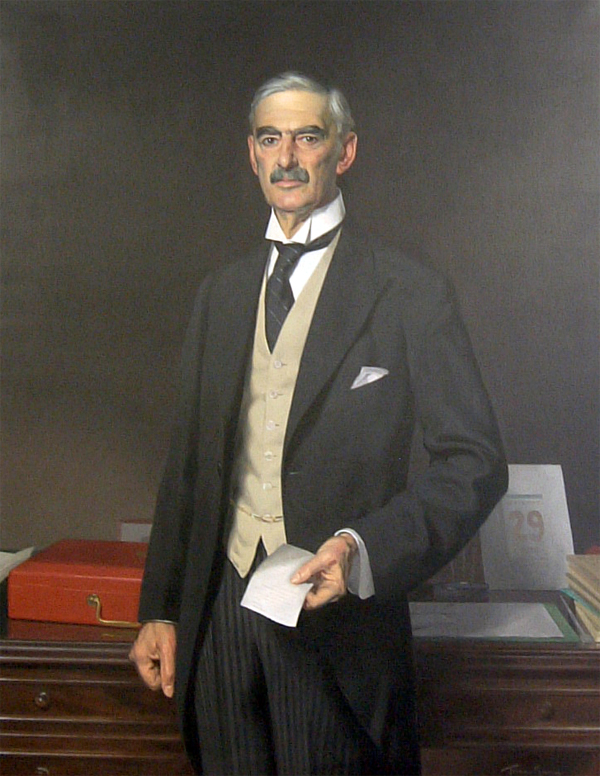

Arthur Neville Chamberlain (18 March 1869 – 9 November 1940)

SUMMARY OF CONTENTS.

GERMAN-POLISH RELATIONS FROM JANUARY 1934 TO JANUARY 1939.

THE governing factor in the relations between Germany and Poland during this period was the German-Polish Agreement of the 26th January, 1934 (No. 1), This agreement, which was valid for ten years, provided that in no circumstances would either party "proceed to the application of force for the purpose of reaching a decision" in any dispute between them. In the five years after the signature of this pact Herr Hitler made a number of speeches friendly to Poland (Nos. 2-8). Poland was "the home of a great, nationally-conscious people" (21st May, 1935). It would be "unreasonable and impossible," so Herr Hitler acknowledged, "to deny a State of such a size as this any outlet to the sea" (7th March, 1936). The agreement "has worked out to the advantage of both sides" (30th January, 1937).

DETERIORATION IN THE EUROPEAN SITUATION RESULTING FROM GERMAN ACTION AGAINST CZECHO-SLOVAKIA ON MARCH 15, 1939.

The position after the German occupation of Czecho-Slovakia was summarized in speeches by the Prime Minister at Birmingham on the 17th March (No. 9) and by Viscount Halifax, Secretary of State for Foreign Affairs, in the House of Lords on the 20th March, 1939 (No. 10). Mr. Chamberlain described the German occupation as "in complete disregard of the principles laid down by the German Government itself," and asked: "Is this the end of an old adventure, or is it the beginning of a new? Is this the last attack upon a small State, or is it to be followed by others?" Lord Halifax stated that the action of the German Government was "a complete repudiation of the Munich Agreement and a denial of the spirit in which the negotiators of that agreement bound themselves to co-operate for a peaceful settlement." On the 23rd March the Prime Minister stated in the House of Commons that His Majesty's Government, while not wishing "to stand in the way of any reasonable efforts on the part of Germany to expand her export trade," was resolved "by all means in our power" to oppose a "procedure under which independent States are subjected to such pressure under threat of force as to be obliged to yield up their independence" (No. 11). In a conversation of the 27th May between Sir Nevile Henderson, His Majesty's Ambassador in Berlin, and Field-Marshal Goring, the Ambassador warned the Field-Marshal that Great Britain and France would be involved in war with Germany if Germany attempted to settle German-Polish differences "by unilateral action such as would compel the Poles to resort to arms to safeguard their independence" (No. 12).

In a speech to the Reichstag on the 28th April, Herr Hitler announced that he had made proposals to the Polish Government that Danzig should return as a Free City into the framework of the Reich, and that Germany should receive a route and railway with extra-territorial status through the Corridor in exchange for a 25-years' pact of non-aggression and a recognition of the existing German-Polish boundaries as "ultimate." On the same day a memorandum to this effect was given to the Polish Government. The German proposals, which had been presented for the first time on the 21st March, 1939, i.e., less than a week after the German occupation of Prague, were now described as "the very minimum which must be demanded from the point of view of German interests." Herr Hitler also claimed that the German-Polish Agreement of January 1934 was incompatible with the Anglo-Polish promises of mutual assistance and therefore was no longer binding (Nos. 13 and 14).

On the 5th May the Polish Government replied to the German Government with an explanation of their point of view. The Polish note repeated the counter-proposals which the Polish Government had put forward as a basis for negotiation in reply to the German proposals, and refuted the German argument that the Anglo-Polish guarantee was in any way incompatible with the German-Polish Agreement (No. 16). The Polish Minister for Foreign Affairs elaborated his country's case in a speech made in the Polish Parliament on the 5th May. The Minister said that the Polish Government regarded the German proposals as a demand for "unilateral concessions." He added that Poland was ready to approach "objectively" and with "their utmost goodwill" any points raised for discussion by the German Government, but that two conditions were necessary if the discussions were to be of real value: (1) peaceful intentions, (2) peaceful methods of procedure ( No. 15).

The Polish memorandum reminded the German Government that no formal reply to the Polish counter-proposals had been received for a month, and that only on the 28th April the Polish Government learned that "the mere fact of the formulation of counter-proposals instead of the acceptance of the verbal German suggestions without alteration or reservation had been regarded by the Reich as a refusal of discussions" (No. 16).

On the 31st March, 1939, the Prime Minister announced the assurance of British and French support to Poland "in the event of any action which clearly threatened Polish independence, and which the Polish Government accordingly considered it vital to resist" (No. 17). An Anglo-Polish communiqué issued on the 6th April recorded the assurances of mutual support agreed upon by the British and Polish Governments, "pending the completion of the permanent agreement" (No. 18). The Agreement of Mutual Assistance was signed on the 25th August. The articles defined the mutual guarantee in case of aggression by a European Power (No. 19).

DEVELOPMENTS IN ANGLO-GERMAN RELATIONS AND IN THE GENERAL BRITISH ATTITUDE TOWARDS THE INTERNATIONAL SITUATION (APRIL—JUNE 1939).

Anglo-German as well as German-Polish relations deteriorated after the German occupation of Czecho-Slovakia. On the 1st April Herr Hitler made a speech at Wilhelmshaven in which he attacked Great Britain and British policy towards Germany, and attempted a justification of German policy (No. 20).

Herr Hitler spoke in the Reichstag on the 28th April announcing the denunciation by Germany of the Anglo-German Naval Agreements (No. 21). On the 27th April a memorandum to this effect was sent to the British Government (No 22). On the 16th June Viscount Halifax again denied to the German Ambassador in London that Great Britain or any other Power was "encircling" Germany (No. 23). A week later (23rd June) His Majesty's Government sent a reasoned protest to the German Government denying the validity of the German unilateral denunciation of the Anglo-German Naval Agreements, and also refuting the arguments of fact (i.e., persistent British hostility to Germany) by which Herr Hitler attempted to justify his denunciation of the Naval Agreements (No. 24).

In view of these facts and of the increasing international tension, Viscount Halifax took the opportunity, in a speech at Chatham House on the 29th June, to define at some length the attitude and policy of Great Britain. He explained the reason for the obligations which Great Britain had undertaken in the Continent of Europe. He discussed Anglo-German relations and stated that Great Britain had no wish to isolate Germany, and that, if Germany wished, "a policy of co-operation" could be adopted at once. "British policy rests on twin foundations of purpose. One is determination to resist force. The other is our recognition of the world's desire to get on with the constructive work of building peace" (No. 25).

DETERIORATION IN THE LOCAL SITUATION AT DANZIG (JUNE 3—JULY 3, 1939).

With the increase of agitation in the Reich the local situation at Danzig rapidly became worse. On the 3rd June the President of the Danzig Senate made accusations against Polish customs inspectors (No. 26). The Polish Government on the 10th June replied with a denial of the accusations and a statement of the legal rights of Poland in relation to Danzig (No. 27). On the 27th June the Polish Vice-Minister for Foreign Affairs told Sir H. Kennard, His Majesty's Ambassador in Warsaw, that a Freicorps was being formed in Danzig (No. 28), and on the 28th and 30th June, and on the 1st July, Mr. Shepherd, His Majesty's Consul-General in Danzig, reported upon military preparations in the city (Nos. 29, 31, 33). On the 30th June, in view of the gravity of the situation, Viscount Halifax suggested consultation between the British, French and Polish Governments for the co-ordination of their plans (No. 30). Meanwhile, the Polish Government maintained a restrained attitude (Nos. 32 and 34).

BRITISH ATTITUDE TOWARDS DEVELOPMENTS IN DANZIG (JULY 10—15, 1939).

On the 10th July, while the situation at Danzig appeared to be becoming critical, the Prime Minister defined the British attitude towards the Danzig problem in a statement in the House of Commons (No. 35). He pointed out that it was before Poland had received any guarantee from Great Britain that the Polish Government, fearing to be faced with unilateral German action, had replied to the German proposals, by putting forward certain counter-proposals, and that the cause of the Polish refusal to accept the German proposals was to be found in the character of these proposals and in the manner and timing of their presentation and not in the British guarantee of Poland.

On the 14th July Sir Nevile Henderson discussed with Baron von Weizsäcker, German State Secretary at the Ministry for Foreign Affairs, a statement by one of the German Under-Secretaries that "Herr Hitler was convinced that England would never fight over Danzig." Sir Nevile Henderson repeated the affirmation already made by His Majesty's Government that, in the event of German aggression, Great Britain would support Poland in resisting force by force (No. 36).

TEMPORARY EASING IN THE DANZIG SITUATION (JULY 19— AUGUST 2).

After the tension in Danzig at the end of June there was a temporary lull in the situation. The Acting British Consul-General at Danzig reported on the 19th July that Herr Forster, the leader of the National Socialist party in Danzig, had stated, after an interview with Herr Hitler, that "nothing will be done on the German side to provoke a conflict," and that the Danzig question could "wait if necessary until next year or even longer" (No. 37). On the 21st July Viscount Halifax instructed Mr. Norton, His Majesty's Chargé d'Affaires at Warsaw, to impress upon the Polish Government the need for caution (No. 38). M. Beck replied, on the 25th July, that the Polish Government was equally anxious for a détente (No. 39). On the previous day Herr Forster had again stated that "the Danzig question could, if necessary, wait a year or more" (No. 40). On the 31st July and the 2nd August, however, Sir H. Kennard reported less hopefully about the position (Nos. 41 and 42).

FURTHER DETERIORATION IN THE SITUATION AT DANZIG (August 4-16).

On the 4th August M. Beck told His Majesty's Chargé d'Affaires at Warsaw that the Danzig Senate had that day informed Polish customs inspectors at four posts in Danzig that henceforward they would not be allowed to carry out their duties. The Polish Government took "a very serious view" of this step (No. 43). Similar news came from Mr. Shepherd at Danzig (No. 44). On the 9th August Sir H. Kennard reported that the Polish attitude was "firm but studiously moderate"; (No. 45). A day later, Sir H. Kennard reported to His Majesty's Government a communication made by the German Government to the Polish Chargé d'Affaires at Berlin on the Danzig question, and the Polish reply to this communication. M. Beck drew the attention of Sir H. Kennard to "the very serious nature of the German démarche as it was the first time that the Reich had directly intervened in the dispute between Poland and the Danzig Senate" (No. 46). The Polish Government in their reply to the German note verbale stated that they would "react to any attempt by the authorities of the Free City which might tend to compromise the rights and interests which Poland possesses there in virtue of her agreements, by the employment of such means and measures as they alone shall think fit to adopt, and will consider any future intervention by the German Government to the detriment of these rights and interests as en act of aggression" (No. 47).

Sir Nevile Henderson on the 15th August discussed with Baron von Weizsäcker the deterioration in the Danzig position, and pointed out that if the Poles "were compelled by any act of Germany to resort to arms to defend themselves, there was not a shadow of doubt that we would give them our full armed support .... Germany would be making a tragic mistake if she imagined the contrary." Baron von Weizsäcker himself observed that "the situation in one respect was even worse than last year, as Mr. Chamberlain could not again come out to Germany." Baron von Weizsäcker also discounted the character of Russian help to Poland and "thought that the U.S.S.R. would even in the end join in sharing the Polish spoils" (No. 48).

Meanwhile, on the 11th August, M. Burckhardt had a conversation with Herr Hitler at Berchtesgaden at the latter's request, in which the question of Danzig and the general European situation were discussed (No. 49). Viscount Halifax, who still hoped that Herr Hitler might avoid war, advised the Polish Government to make it clear that they remained ready for negotiations over Danzig (Nos. 50 and 51).

TREATMENT OF THE GERMAN MINORITY IN POLAND (AUGUST 24-27).

During the course of the correspondence outlined in this section, Sir H. Kennard reported that the German press campaign about the persecution of the German minority in Poland was a "gross distortion and exaggeration of the facts" (No. 52). On the 26th August Sir H. Kennard reported frontier incidents which had been provoked by the Germans. They had not caused the Poles to change their "calm and strong attitude of defence" (No. 53). Reports of unfounded German allegations against the Poles were also sent by Sir H. Kennard on the 26th and 27th August (Nos. 54 and 55).

DEVELOPMENTS LEADING IMMEDIATELY TO THE OUTBREAK OF HOSTILITIES BETWEEN GREAT BRITAIN AND GERMANY (AUGUST 24—SEPTEMBER 3).

The Prime Minister's letter to Herr Hitler (August 22) and Herr Hitler's interview with Sir Nevile Henderson (August 23).

On the 22nd August, after the publication of the news of Herr von Ribbentrop's visit to Moscow to sign a non-aggression pact with the U.S.S.R., the Prime Minister sent a personal letter to Herr Hitler. Mr. Chamberlain once again gave a clear statement of the British obligations to Poland, and stated that "whatever may prove to be the nature of the German-Soviet Agreement, it cannot alter Great Britain's obligation." He added that "it has been alleged that, if His Majesty's Government had made their position more clear in 1914, the great catastrophe would have been avoided. Whether or not there is any force in that allegation, His Majesty's Government are resolved that on this occasion there shall be no such tragic misunderstanding" (No. 56) On the 23rd August Sir Nevile Henderson reported his first interview with Herr Hitler earlier in the day. Herr Hitler was "excitable and uncompromising"; his language was "violent and exaggerated both as regards England and Poland." Herr Hitler observed, in reply to His Majesty's Ambassador's repeated warnings that direct action against Poland would mean war with Great Britain, that "Germany had nothing to lose, and Great Britain much; that he did not desire war, but would not shrink from it if it was necessary, and that his people were much more behind him than last September (No. 57).

Herr Hitler was calmer at a second talk, but no less uncompromising. He put the whole responsibility for war on Great Britain, and maintained that Great Britain was "determined to destroy and exterminate Germany. He was, he said, 50 years old; he preferred war now to when he would be 55 or 60." He said that "England was fighting for lesser races, whereas he was fighting only for Germany" (No. 58).

The German reply to the Prime Minister's letter was given to His Majesty's Ambassador on the 23rd August. Herr Hitler stated that the British promise to assist Poland would make no difference to the determination of the Reich to safeguard German interests, and that the precautionary British military measures announced in the Prime Minister's letter of the 22nd August would be followed by the mobilisation of the German forces (No. 60).

Text of the German-Soviet Non-Aggression Pact (August 23) (No. 61).

Appointment of Herr Forster as Head of the State of the Free City of Danzig (August 23).

Herr Forster was declared by decree of the Danzig Senate, on the 23rd August, Head of the State (Staatsoberhaupt) of the Free City of Danzig (No. 62). The Polish Government protested to the Senate against the illegality of this appointment (No. 63).

Speeches by the Prime Minister and Viscount Halifax on the Danzig and general German-Polish situation and the determination of Great Britain to honour British obligations to Poland (August 24) (Nos. 64 and 65).

Attempts by the Polish Government to establish contact with the

German Government (August 24).

In view of the increasing tension in Danzig, M. Beck told Sir H. Kennard that he considered the situation "most grave," and that he had asked the Polish Ambassador in Berlin to seek an immediate interview with the German State Secretary (No. 66). This interview could not, however, be arranged, since Baron von Weizsäcker was at Berchtesgaden, but the Polish Ambassador had an interview in the afternoon of the 24th August with Field-Marshal Göring. The Field-Marshal regretted that "his policy of maintaining friendly relations with Poland should have come to nought, and admitted that he no longer had influence to do much in the matter." The Field-Marshal hinted that Poland should abandon her alliance with Great Britain, and left the Polish Government with the impression that Germany was aiming at a free hand in Eastern Europe (No. 67).

Interview between Sir N. Henderson and Herr Hitler, and German "verbal communication" of August 25.

On the 25th August Herr Hitler sent for Sir Nevile Henderson and asked him to fly to London to "put the case" to His Majesty's Government. The "case," which included an offer of friendship with Great Britain, once the Polish question had been solved, was contained in a verbal communication made to His Majesty's Ambassador (No. 68). During the discussion with Herr Hitler, Sir Nevile Henderson stated once more that Great Britain "could not go back on her word to Poland," and would insist upon a settlement by negotiation. Herr Hitler refused to guarantee a negotiated settlement on the ground that "Polish provocation might at any moment render German intervention to protect German nationals inevitable" (No. 69).

Correspondence between the British and Polish Governments, August 25-27.

On the 25th August Viscount Halifax suggested to the Polish Government the establishment of a corps of neutral observers, who would enter upon their functions if it were found possible to open negotiations (No. 70. He also suggested the possibility of negotiating over an exchange of populations (No. 71, p. 160). M. Beck raised no objection in principle to either proposal (No. 72).

Reply of His Majesty's Government, dated August 28, to Herr Hitler's communications of August 23 and 25 (No. 60 and No. 68): interview of August 28 between Sir Nevile Henderson and Herr Hitler: speech of the Prime Minister in the House of Commons on August 29.

On the 28th August Viscount Halifax informed the Polish Government through Sir H. Kennard that in the British reply to Herr Hitler "a clear distinction" would be drawn between "the method of reaching agreement on German-Polish differences and the nature of the solution to be arrived at. As to the method, we (His Majesty's Government) wish to express our clear view that direct discussion on equal terms between the parties is the proper means" (No. 73).

The reply of His Majesty's Government, suggesting direct discussion between the German and Polish Governments, was presented to Herr Hitler by Sir N. Henderson on the 28th August (No. 74). His Majesty's Government stated they had "already received a definite assurance from the Polish Government that they are prepared to enter into discussions," and that, if such direct discussion led, as they hoped, to agreement, "the way would be open to the negotiation of that wider and more complete understanding between Great Britain and Germany which both countries desire." In his interview of the 28th August with Herr Hitler, Sir N. Henderson repeated the British readiness to reach an Anglo-German understanding, "but only on the basis of a peaceful and freely negotiated solution of the Polish question." Sir Nevile Henderson pointed out to Herr Hitler that "it lay with him (Herr Hitler) as to whether he preferred a unilateral solution which would mean war as regards Poland, or British friendship." Herr Hitler, who said that "his army was ready and eager for battle," would not answer at once whether he would negotiate directly with Poland (No. 75)

On the 29th August the Prime Minister once more explained in the House of Commons the British standpoint (No. 77).

Interview of August 29 between Sir N. Henderson and Herr Hitler, and German demand for the arrival of a Polish representative in Berlin by August 30.

At 7:15 p. m. on the 29th August Sir N. Henderson received from Herr Hitler the German answer that the German Government was prepared to accept the British proposal for direct German-Polish negotiations, but counted on the arrival of a Polish plenipotentiary by the 30th August (No. 78.). The British Ambassador remarked that the latter demand "sounded like an ultimatum," but, after some heated remarks, both Herr Hitler and Herr von Ribbentrop assured the Ambassador "that it was only intended to stress the urgency of the moment" (No. 79). The interview was "of a stormy character." Sir N. Henderson thought that Herr Hitler was "far less reasonable" than on the 28th August ( No. 80).

At 4 a. m. on the 30th August Sir N. Henderson, on instructions from His Majesty's Government, informed the German Government that it would be "unreasonable to expect the British Government to produce a Polish representative in Berlin" by the 30th August, and that "the German Government must not expect this" (Nos. 81 and 82).

Exchange of correspondence between His Majesty's Government and the Polish Government on August 30.

Sir H. Kennard also reported his opinion that the Polish Government could not be induced to send a representative immediately to Berlin to discuss a settlement on the basis proposed by Herr Hitler. "They would certainly sooner fight and perish rather than submit to such humiliation, especially after the examples of Czecho-Slovakia, Lithuania and Austria" (No. 84). On this same day the Polish Government gave their assurance, in reply to advice from Viscount Halifax, to avoid any kind of provocation (No. 85), that they had no intention of provoking any incidents, in spite of the provocation at Danzig, which was becoming "more and more intolerable" (No. 86).

Exchange of correspondence between the British and German Governments with regard to the opening of direct German-Polish negotiations (August 30).

At 2:45 p. m. and again at 5:30 p. m. on the 30th August His Majesty's Government instructed Sir N. Henderson to inform the German Government of the representations which the British Government had made in Warsaw for the avoidance of all frontier incidents and urged the German Government to reciprocate (Nos. 83 and 87). They repeated at 6:50 p. m., in view of the German insistence on the point, that it was "wholly unreasonable" for the German Government to insist upon the arrival in Berlin of a Polish representative with full powers to receive German proposals, and that they could not advise the Polish Government in this sense. They suggested the normal procedure of giving the Polish Ambassador the German proposals for transmission to Warsaw (No. 88).

At midnight on the 30th-31st August Sir N. Henderson handed to Herr von Ribbentrop the full British reply to the German letter of the 28th August (No. 78). The reply noted the German Government's acceptance of the British proposal for direct German-Polish discussions, and of the "position of His Majesty's Government as to Poland's vital interests and independence." The reply also noted that the German Government accepted "in principle the condition that any settlement should be made the subject of an international guarantee." His Majesty's Government stated that they were informing the Polish Government of the German Government's reply. "The method of contact and arrangements for discussions must obviously be agreed with all urgency between the German and Polish Governments, but in His Majesty's Government's view it would be impracticable to establish contact so early as to-day (i.e., the 30th August) (No. 89).

The British reply was also telegraphed to the Polish Government, and Viscount Halifax hoped that "provided the method and general arrangement for discussions can be satisfactorily agreed," the Polish Government, which had authorised His Majesty's Government to say that they were prepared to enter into direct discussions, would be ready to do so without delay (No. 90)

In his interview at midnight the 30th-31st August with Herr von Ribbentrop, Sir N. Henderson suggested that the German Government should adopt the normal procedure of making contact with the Polish Government, i.e., that when the German proposals were ready the Polish Ambassador should be invited to call and to receive these proposals "for transmission to his Government with a view to the immediate opening of negotiations."

"Herr von Ribbentrop's reply was to produce a lengthy document which he read out in German aloud at top-speed." When His Majesty's Ambassador asked for the text of the proposals in the document, he was told that it was "now too late," as a Polish representative had not arrived in Berlin by midnight (the 30-31st August). Sir N. Henderson described this procedure as an "ultimatum," in spite of the assurances previously given by the German Government. He asked why Herr von Ribbentrop could not adopt the normal procedure, give him a copy of the proposals, and ask the Polish Ambassador to call on him (Herr von Ribbentrop) to receive them. "In the most violent terms Herr von Ribbentrop said that he would never ask the Polish Ambassador to visit him," though he hinted that it might be different if the Polish Ambassador asked for an interview (No. 92)

Exchange of correspondence between the British and Polish Governments on August 31 with regard to direct negotiations.

On hearing of the reply of His Majesty's Government to the German Government (No. 89) on the subject of direct German-Polish negotiations, M. Beck said that he would do "everything possible to facilitate the efforts of His Majesty's Government." He promised the "considered reply of his Government" by midday on the 31st August (No. 93, p. 189), Later on the 31st August Viscount Halifax advised the Polish Government immediately to instruct the Polish Ambassador in Berlin to say that he was ready to transmit to his Government any proposals made by the German Government so that they (the Polish Government) "may at once consider them and make suggestions for early discussions" (No. 95).

At 630 P.M. on the 31st August Sir H. Kennard communicated to London the formal Polish confirmation of the readiness of the Polish Government to enter into direct discussions with the German Government on the basis proposed by Great Britain ( No. 97). M. Beck said that "he would now instruct M. Lipski [Polish Ambassador in Berlin] to seek an interview either with the (German) Minister for Foreign Affairs or the State Secretary" in order to establish contact for the initiation of direct discussions, but that the Polish Ambassador would not be authorised to receive a document containing the German proposals, since, "in view of past experience, it might be accompanied by some sort of ultimatum." In M. Beck's view "it was essential that contact should be made, in the first instance," for the discussion of details "as to where, with whom, and on what basis negotiations should be commenced" (No. 96).

German proposals for German-Polish settlement, presented to the British Ambassador in Berlin at 9:15 P.M. on August 31, and German invasion of Poland on September 1.

It was not until 9:15 p. m. on the 31st August that the German Government gave Sir N. Henderson a copy of their proposals, which had been read to him so rapidly by Herr von Ribbentrop on the previous night. The German Government stated that the note contained the sixteen points of their proposed settlement, but that, as the Polish plenipotentiary, with powers "not only to discuss but to conduct and conclude negotiations," had not arrived in Berlin, they regarded their proposals as "to all intents and purposes rejected (No. 98). At 11 P.M. Viscount Halifax telephoned instructions to Sir N. Henderson to inform the German Government that the Polish Government were taking steps to establish contact with them through the Polish Ambassador in Berlin (No. 99). At 9 P.M. British summer time the German Government had, however, broadcast their proposals together with the statement that they regarded them as having been rejected. They had, however, never been communicated to the Polish Government and all means of communication between the Polish Ambassador in Berlin and the Polish Government had been cut off.

As a final attempt to meet the German demands, Viscount Halifax telegraphed to Sir H. Kennard in the night of the 31st August-1st September his view that the Polish Ambassador in Berlin might receive a document for transmission to his Government and might say that "(a) if it contained anything like an ultimatum, the Polish Government would certainly be unable to discuss on such a basis; and (b) that, in any case, in the view of the Polish Government, questions as to the venue of the negotiations, the basis on which they should be held, and the persons to take part in them, must be discussed and decided between the two Governments" (No. 100).

In answer to this telegram, Sir H. Kennard replied on the 1st September that M. Lipski "had already called on the German Foreign Minister at 6:30 p. m." on the 31st August. "In view of this fact, which was followed by the German invasion of Poland at dawn to-day (1st September), it was clearly useless for me to take the action suggested" (No. 101).

These facts were announced to the House of Commons by the Prime Minister on the 1st September (No. 105). A further "explanatory note, upon the actual course of events," reprinted from White Paper (Misc. No. 8 (1939), Cmd. 6102) (No. 104) should be read in connexion with Herr Hitler's version of events as given in his speech of the 1st September to the Reichstag (No. 106) and in his proclamation to the German army (No. 107).

Reunion of Danzig with the Reich (September 1).

On the 1st September Herr Forster announced in a proclamation to the people of Danzig the reunion of Danzig with the Reich. He telegraphed an account of his action to Herr Hitler, who replied at once accepting the reunion and ratifying the so called legal act by which it was brought about (No. 108).

Action taken by His Majesty's Government after the receipt of news of the German attack on Poland (September 1-3).

On the 1st September, after His Majesty's Government had received news of the German invasion of Poland, Viscount Halifax instructed Sir N. Henderson to inform the German Government that the Governments of the United Kingdom and France considered that the German action had "created conditions (viz., an aggressive act of force against Poland threatening the independence of Poland) which call for the implementation by the Governments of the United Kingdom and France of the undertaking to Poland to come to her assistance." Unless the German Government suspended all aggressive action against Poland, and promptly withdrew their forces from Polish territory, His Majesty's Government in the United Kingdom would "without hesitation fulfill their obligations to Poland." Sir N. Henderson was authorised to explain, if asked, that this communication was "in the nature of a warning," and was "not to be considered as an ultimatum," but Viscount Halifax added, for Sir N. Henderson's own information, that, "if the German reply is unsatisfactory, the next stage will be either an ultimatum with time-limit or an immediate declaration of war" (Nos. 109 and 110).

On the night of the 1st-2nd September Sir N. Henderson reported that he had made the necessary communication to Herr von Ribbentrop at 9:30 p. m. and had asked for an immediate answer. Herr von Ribbentrop replied that he would submit the communication to Herr Hitler (No. 111). Meanwhile, on the 1st September, the Polish Government announced to His Majesty's Government that, although the Polish Ambassador in Berlin had seen Herr von Ribbentrop at 6:30 p. m. on the 31st August, and had expressed the readiness of the Polish Government to enter into direct negotiations, Polish territory had been invaded, and the Polish Government had therefore been compelled to break off relations with Germany (No. 112) (see also Nos. 113 and 115). At 10:50 a. m. on the 1st September Viscount Halifax sent for the German Chargé d'Affaires in London, drew his attention to the reports which had reached His Majesty's Government about German action against Poland and informed him that these reports "created a very serious situation" (No. 14).

The Prime Minister on the 2nd September made a statement in the House of Commons, in the course of which he said that no answer had been received to the message sent to the German Government on the 1st September, requesting the cessation of German aggression and the withdrawal of German troops from Poland. The Prime Minister also informed the House of proposals put forward by the Italian Government for a cessation of hostilities, but made it clear that His Majesty's Government could not take part in any conference unless German aggression ceased and German troops were withdrawn from Poland (No. 116). At 5 a. m. on the 3rd September Sir N. Henderson was instructed to ask for an interview at 9 a. m. with Herr von Ribbentrop and to inform him that, although His Majesty's Government had warned the German Government of the results which would follow if Germany did not suspend all aggressive action against Poland, no answer had been received from the German Government. His Majesty's Government therefore stated that unless satisfactory assurances were received from the German Government not later than 11 a. m. a state of war would exist between the United Kingdom and Germany (No. 118).

At 11:20 a. m. on the 3rd September the German Government replied with a statement of their case, concluding with the suggestion that His Majesty's Government desired the destruction of the German people, and with the words "we shall answer any aggressive action on the part of England with the same weapons and in the same form" (No. 119). Shortly afterwards the Prime Minister announced in the House of Commons that Great Britain was at war with Germany (No. 120) This section of the documents concludes with Herr Hitler's proclamations of the 3rd September to the German people and to the German army (No. 121).

ATTEMPTS AT MEDIATION BY OTHER STATES.

The full text is given of the exchange of messages between the President of the United States of America and His Majesty the King of Italy (Nos. 122 and 123); the President of the United States of America and the President of Poland; and the messages of the President of the United States of America to Herr Hitler (Nos. 124-127); the broadcast appeal of the 23rd August by His Majesty the King of the Belgians in the name of the Heads of States of the Oslo Group of Powers and the replies (Nos. 128-133); the joint offer of mediation by His Majesty the King of the Belgians, and Her Majesty the Queen of the Netherlands and the replies (Nos. 134-138); the broadcast appeal of the 24th August by His Holiness the Pope with the reply of His Majesty's Government and telegrams describing a last peace attempt by the Pope on the 31st August, together with His Majesty's Government's reaction, are also given in full (Nos. 139-142).

A communiqué issued by the official Italian Stefani news agency on the 4th September recording the efforts made by the Italian Government to maintain peace is published as the last document in this chapter (No. 143).

The final Document (No. 144) is the Prime Minister's broadcast of the 4th September, 1939, to the German People.

LIST OF PRINCIPAL PERSONS MENTIONED IN THE DOCUMENTS, SHOWING THEIR OFFICIAL POSITIONS.

UNITED KINGDOM

Prime Minister ................................. Mr. Neville Chamberlain.

Secretary of State for Foreign Affairs ......... Viscount Halifax.

Secretary of State for Foreign Affairs

in 1914 ...................................... Sir Edward Grey.

Secretary of State for Foreign Affairs

in 1935 ...................................... Sir Samuel Hoare.

Leader of His Majesty's Opposition ............ Mr. C. R. Atlee.

Polish Ambassador .............................. Count Edward Raczynski.

German Ambassador .............................. Herr von Dirksen.

German Chargé d'Affaires ....................... Dr. Kordt

FRANCE.

President of the Council ....................... M. Daladier.

POLAND.

Polish Statesman ............................... (The late) Marshal

Pilsudski

Polish Statesman and Inspector-General

of Polish Army ............................... Marshal Smigly-Rydz.

Minister for Foreign Affairs ................... M. Josef Beck.

Vice-Minister for Foreign Affairs .............. M. Arciszewski.

British Ambassador ............................. Sir. H. Kennard.

British Chargé d'Affaires ...................... Mr. Norton.

DANZIG.

League of Nations High Commissioner ............ M. Burckhardt.

Polish Commissioner-General .................... M. Chodaki.

Nazi Gauleiter ................................. Herr Forster.

President of Senate ............................ Herr Greiser.

State Counsellor dealing with Foreign Relations .............. Dr. Boettcher.

British Consul-General ......................... Mr. G. Sheperd.

Acting British Consul-General (from 10th July) . Mr. F. M. Sheperd.

GERMANY.

Prime Minister of Prussia, &c. ................. Field-Marshal Göring.

Nazi leader and Deputy to the Führer ........... Herr Hess.

Minister for Propaganda ........................ Dr. Goebbels.

Minister for Foreign Affairs ................... Herr von Ribbentrop.

State Secretary at Ministry for Foreign Affairs Baron ............ von Weizsäcker.

Under-Secretary at Ministry for Foreign Affairs ...................... Dr. Keppler.

Official Interpreter at Ministry for

Foreign Affairs .............................. Dr. Schmidt.

Former Minister for Foreign Affairs ............ Freiherr von Neurath.

British Ambassador ............................. Sir Nevile Henderson.

Polish Ambassador .............................. M. Josef Lipski.

SOVIET UNION.

Leading Statesman .............................. M. Stalin.

Prime Minister and Minister for Foreign Affairs ...................M. Molotov.

CZECHO-SLOVAKIA.

Former President ............................... Dr. Benes.

President ( after the Munich Agreement) ........ Dr. Hacha.

ITALY.

Duce British Ambassador ........................ Signor Mussolini.

British Minister ............................... Sir P. Loraine.

HOLY SEE

British Minister ............................... Mr. Osborne.

BELGIUM.

British Ambassador ............................. Sir R. Clive.

NETHERLANDS.

British Chargé d'Affaires ...................... Sir N. Bland.

LITHUANIA.

British Chargé d'Affaires ...................... Mr. Preston.

DOCUMENTS CONCERNING GERMAN-POLISH RELATIONS AND THE OUTBREAK OF HOSTILITIES BETWEEN GREAT BRITAIN AND GERMANY ON SEPTEMBER 3, 1939.

GERMAN-POLISH AGREEMENT

No. 1.

TEXT OF GERMAN-POLISH AGREEMENT OF JANUARY 26, 1934.

(Translation.)

The German Government and the Polish Government consider that the time has come to introduce a new phase in the political relations between Germany and Poland by a direct understanding between State and State. They have, therefore, decided to lay down the principles for the future development of these relations in the present declaration.

The two Governments base their action on the fact that the maintenance and guarantee of a lasting peace between their countries is an essential pre-condition for the general peace of Europe.

They have therefore decided to base their mutual relations on the principles laid down in the Pact of Paris of the 17th August, 1928, and propose to define more exactly the application of these principles in so far as the relations between Germany and Poland are concerned.

Each of the two Governments, therefore, lays it down that the international obligations undertaken by it towards a third party do not hinder the peaceful development of their mutual relations, do not conflict with the present declaration, and are not affected by this declaration. They establish, moreover, that this declaration does not extend to those questions which under international law are to be regarded exclusively as the internal concern of one of the two States.

Both Governments announce their intention to settle directly all questions of whatever sort which concern their mutual relations.

Should any disputes arise between them and agreement thereon not be reached by direct negotiation, they will in each particular case, on the basis of mutual agreement, seek a solution by other peaceful means, without prejudice to the possibility of applying, if necessary, those methods of procedure in which provision is made for such cases in other agreements in force between them. In no circumstances, however, will they proceed to the application of force for the purpose of reaching a decision in such disputes.

The guarantee of peace created by these principles will facilitate the great task of both Governments of finding a solution for problems of political, economic and social kinds, based on a just and fair adjustment of the interests of both parties.

Both Governments are convinced that the relations between their countries will in this manner develop fruitfully, and will lead to the establishment of a neighbourly relationship which will contribute to the well-being not only of both their countries, but of the other peoples of Europe as well.

The present declaration shall be ratified, and the instruments of ratification shall be exchanged in Warsaw as soon as possible.

The declaration is valid for a period of ten years, reckoned from the day of the exchange of the instruments of ratification.

If the declaration is not denounced by one of the two Governments six months before the expiration of this period, it will continue in force, but can then be denounced by either Government at any time on notice of six months being given. Made in duplicate in the German and Polish languages.

Berlin, January 26, 1934.

For the German Government:

FREIHERR VON NEURATH.

For the Polish Government

JOSEF LIPSKI.

HITLER ON GERMAN-POLISH RELATIONS

STATEMENTS MADE BY HERR HITLER SINCE THE GERMAN-POLISH AGREEMENT RECORDING HIS SATISFACTION AT THE IMPROVEMENT IN GERMAN-POLISH RELATIONS.

No. 2.

Reichstag Speech, May 21, 1935.

(Translation.)

"WE recognize, with the understanding and the heartfelt friendship of true Nationalists, the Polish State as the home of a great, nationally-conscious people."

"The German Reich and, in particular, the present German Government, have no other wish than to live on friendly and peaceable terms with all neighbouring States."

No. 3.

Reichstag Speech, March 7, 1936.

(Translation.)

"I would like the German people to learn to see in other nations historical realities which a visionary may well like to wish away, but which cannot be wished away. I should like them to realise that it is unreasonable to try and bring these historical realities into opposition with the demands of their vital interests and to their understandable claims to live. I would therefore like the German people to understand the inner motives of National Socialist foreign policy, which finds it painful that the outlet to the sea of a people of 35 millions is situated on territory formerly belonging to the Reich, but which recognises that it is unreasonable and impossible to deny a State of such a size as this any outlet to the sea at all .... It is possible that politicians, particularly by invoking might, may carry out such violations of national interests; but the more frequently this happens, the greater becomes the pressure for an outlet of the excited and constrained powers and energies."

No. 4.

Reichstag Speech, January 30, 1937.

(Translation.)

"By a series of agreements we have removed existing tensions and thereby contributed considerably to an improvement in the European atmosphere. I merely recall our agreement with Poland, which has worked out to the advantage of both sides .... And to my own fellow-citizens I would say that the Polish nation and the Polish State have also become a reality .... The peoples of these States (i.e., Italy, Poland and the Balkan States) desire to live and they will live."

No. 5.

Reichstag Speech, February 20, 1938.

(Translation.)

"It fills us, in the fifth year following the first great foreign political agreement of the Reich, with sincere gratification to be able to establish that in our relationship to the State with which we had perhaps the greatest differences, not only has there been a détente, but that in the course of these years a constant improvement in relations has taken place. I know perfectly well that this was above all attributable to the circumstance that at the time there was no Western parliamentarism in Warsaw, but a Polish field-marshal, who as an eminent personality felt the significance, so important to Europe, of such a Germano-Polish détente. This good work, which had been doubted by so many at the time, has meanwhile stood the test, and I may say that, since the League of Nations finally gave up its perpetual attempts to unsettle Danzig and appointed in the new commissioner a man of great personal attainments, this most dangerous spot from the point of view of European peace has entirely lost its menacing character. The Polish State respects the national conditions in this State, and both the city of Danzig and Germany respect Polish rights. And so the way to a friendly understanding has been successfully paved, an understanding which, starting from Danzig, has to-day succeeded in spite of the attempts of certain mischief-makers in finally taking the poison out of the relations between Germany and Poland and transforming them into a sincere, friendly co-operation."

No. 6.

Speech at Nuremberg, September 14, 1938.

(Translation.)

"In Poland a great patriot and a great statesman was ready to make an accord with Germany; we immediately proceeded to action and completed an agreement which was of greater importance to the peace of Europe than all the chattering in the temple of the League of Nations at Geneva."

No. 7.

Speech in the Sportpalast, September 26, 1938.

(Translation.)

"The most difficult problem with which I was confronted was that of our relations with Poland. There was a danger that Poles and Germans would regard each other as hereditary enemies. I wanted to prevent this. I know well enough that I should not have been successful if Poland had had a democratic Constitution. For these democracies which indulge in phrases about peace are the most bloodthirsty war agitators. In Poland there ruled no democracy, but a man; and with him I succeeded, in precisely twelve months, in coming to an agreement which, for ten years in the first instance, entirely removed the danger of a conflict. We are all convinced that this agreement will bring lasting pacification. We realise that here are two peoples which must live together and neither of which can do away with the other. A people of 33 millions will always strive for an outlet to the sea. A way for understanding, then, had to be found; it has been found; and it will be ever further extended. Certainly things were hard in this area. The nationalities and small national groups frequently quarrelled among themselves.

But the main fact is that the two Governments, and all reasonable and clear-sighted persons among the two peoples and in the two countries, possess the firm will and determination to I improve their relations. It was a real work of peace, of more worth than all the chattering in the League of Nations Palace at Geneva."

No. 8.

Reichstag Speech, January 30, 1939.

(Translation.)

"We have just celebrated the fifth anniversary of the conclusion of our non-aggression pact with Poland. There can scarcely be any difference of opinion to-day among the true friends of peace with regard to the value of this agreement. One only needs to ask oneself what might have happened to Europe if this agreement, which brought such relief, had not been entered into five years ago. In signing it, this great Polish marshal and patriot rendered his people just as great a service as the leaders of the National Socialist State rendered the German people. During the troubled months of the past year the friendship between Germany and Poland was one of the reassuring factors in the political life of Europe."

DETERIORATION IN EUROPEAN SITUATION RESULTING FROM GERMAN ACTION AGAINST CZECHO-SLOVAKIA ON MARCH 15, 1939.

No. 9.

Speech by the Prime Minister at Birmingham on March 17, 1939.

I HAD intended to-night to talk to you upon a variety of subjects, upon trade and employment, upon social service, and upon finance. But the tremendous events which have been taking place this week in Europe have thrown everything else into the background, and I feel that what you, and those who are not in this hall but are listening to me, will want to hear is some indication of the views of His Majesty's Government as to the nature and the implications of those events.

One thing is certain. Public opinion in the world has received a sharper shock than has ever yet been administered to it, even by the present regime in Germany. What may be the ultimate effects of this profound disturbance on men's minds cannot yet be foretold, but I am sure that it must be far-reaching in its results upon the future. Last Wednesday we had a debate upon it in the House of Commons. That was the day on which the German troops entered Czecho-Slovakia, and all of us, but particularly the Government, were at a disadvantage because the information that we had was only partial; much of it was unofficial. We had no time to digest it, much less to form a considered opinion upon it. And so it necessarily followed that I, speaking on behalf of the Government, with all the responsibility that attaches to that position, was obliged to confine myself to a very restrained and cautious exposition, on what at the time I felt I could make but little commentary. And, perhaps naturally, that somewhat cool and objective statement gave rise to a misapprehension, and some people thought that because I spoke quietly, because I gave little expression to feeling, therefore my colleagues and I did not feel strongly on the subject. I hope to correct that mistake to-night.

But I want to say something first about an argument which has developed out of these events and which was used in that debate, and has appeared since in various organs of the press. It has been suggested that this occupation of Czecho-Slovakia was the direct consequence of the visit which I paid to Germany last autumn, and that, since the result of these events has been to tear up the settlement that was arrived at at Munich, that proves that the whole circumstances of those visits were wrong. It is said that, as this was the personal policy of the Prime Minister, the blame for the fate of Czecho-Slovakia must rest upon his shoulders. That is an entirely unwarrantable conclusion The facts as they are to-day cannot change the facts as they were last September. If I was right then, I am still right now. Then there are some people who say: "We considered you were wrong in September, and now we have been proved to be right."

Let me examine that. When I decided to go to Germany I never expected that I was going to escape criticism. Indeed,; I did not go there to get popularity. I went there first and foremost because, in what appeared to be an almost desperate situation, that seemed to me to offer the only chance of averting a European war. And I might remind you that, when it was first announced that I was going, not a voice was raised in criticism. Everyone applauded that effort. It was only later, when it appeared that the results of the final settlement fell short of the expectations of some who did not fully appreciate the facts-it was only then that the attack began, and even then it was not the visit, it was the terms of settlement that were disapproved.

Well, I have never denied that the terms which I was able to secure at Munich were not those that I myself would have desired. But, as I explained then, I had to deal with no new problem. This was something that had existed ever since the Treaty of Versailles-a problem that ought to have been solved long ago if only the statesmen of the last twenty years had taken broader and more enlightened views of their duty. It had become like a disease which had been long neglected, and a surgical operation was necessary to save the life of the patient.

After all, the first and the most immediate object of my visit was achieved. The peace of Europe was saved; and, if it had not been for those visits, hundreds of thousands of families would to-day have been in mourning for the flower of Europe's best manhood. I would like once again to express my grateful thanks to all those correspondents who have written me from all over the world to express their gratitude and their appreciation of what I did then and of what I have been trying to do since.

Really I have no need to defend my visits to Germany last autumn, for what was the alternative? Nothing that we could have done, nothing that France could have done, or Russia could have done could possibly have saved Czecho-Slovakia from invasion and destruction. Even if we had subsequently gone to war to punish Germany for her actions, and if after the frightful losses which would have been inflicted upon all partakers in the war we had been victorious in the end, never could we have reconstructed Czecho-Slovakia as she was framed by the Treaty of Versailles.

But I had another purpose, too, in going to Munich. That was to further the policy which I have been pursuing ever since I have been in my present position-a policy which is sometimes called European appeasement, although I do not think myself that that is a very happy term or one which accurately describes its purpose. If that policy were to succeed, it was essential that no Power should seek to obtain a general domination of Europe; but that each one should be contented to obtain reasonable facilities for developing its own resources, securing its own share of international trade, and improving the conditions of its own people. I felt that, although that might well mean a clash of interests between different States, nevertheless, by the exercise of mutual goodwill and understanding of what were the limits of the desires of others, it should be possible to resolve all differences by discussion and without armed conflict. I hoped in going to Munich to find out by personal contact what was in Herr Hitler's mind, and whether it was likely that he would be willing to co-operate in a programme of that kind. Well, the atmosphere in which our discussions were conducted was not a very favourable one, because we were in the middle of an acute crisis; but, nevertheless, in the intervals between more official conversations I had some opportunities of talking with him and of hearing his views, and I thought that results were not altogether unsatisfactory.

When I came back after my second visit I told the House of Commons of a conversation I had had with Herr Hitler, of which I said that, speaking with great earnestness, he repeated what he had already said at Berchtesgaden-namely, that this was the last of his territorial ambitions in Europe, and that he had no wish to include in the Reich people of other races than German. Herr Hitler himself confirmed this account of the conversation in the speech which he made at the Sportpalast in Berlin, when he said: "This is the last territorial claim which I have to make in Europe." And a little later in the same speech he said: "I have assured Mr. Chamberlain, and I emphasise it now, that when this problem is solved Germany has no more territorial problems in Europe." And he added: "I shall not be interested in the Czech State any more, and I can guarantee it. We don't want any Czechs any more."

And then in the Munich Agreement itself, which bears Herr Hitler's signature, there is this clause: "The final determination of the frontiers will be carried out by the international commission"-the final determination. And, lastly, in that declaration which he and I signed together at Munich, we declared that any other question which might concern our two countries should be dealt with by the method of consultation.

Well, in view of those repeated assurances, given voluntarily to me, I considered myself justified in founding a hope upon them that once this Czecho-Slovakian question was settled, as it seemed at Munich it would be, it would be possible to carry farther that policy of appeasement which I have described. But, notwithstanding, at the same time I was not prepared to relax precautions until I was satisfied that the policy had been established and had been accepted by others, and therefore, after Munich, our defence programme was actually accelerated, and it was expanded so as to remedy certain weaknesses which had become apparent during the crisis. I am convinced that after Munich the great majority of British people shared my hope, and ardently desired that that policy should be carried further. But to-day I share their disappointment, their indignation, that those hopes have been so wantonly shattered.

How can these events this week be reconciled with those assurances which I have read out to you? Surely, as a joint signatory of the Munich Agreement, I was entitled, if Herr Hitler thought it ought to be undone, to that consultation which is provided for in the Munich declaration. Instead of that he has taken the law into his own hands. Before even the Czech President was received, and confronted with demands which he had no power to resist, the German troops were on the move, and within a few hours they were in the Czech capital.

According to the proclamation which was read out in Prague yesterday, Bohemia and Moravia have been annexed to the German Reich. Non-German inhabitants, who, of course, include the Czechs, are placed under the German Protector in the German Protectorate. They are to be subject to the political, military and economic needs of the Reich. They are called self-governing States, but the Reich is to take charge of their foreign policy, their customs and their excise, their bank reserves, and the equipment of the disarmed Czech forces. Perhaps most sinister of all, we hear again of the appearance of the Gestapo, the secret police, followed by the usual tale of wholesale arrests of prominent individuals, with consequences with which we are all familiar.

Every man and woman in this country who remembers the fate of the Jews and the political prisoners in Austria must be filled to-day with distress and foreboding. Who can fail to feel his heart go out in sympathy to the proud and brave people who have so suddenly been subjected to this invasion, whose liberties are curtailed, whose national independence has gone? What has become of this declaration of "No further territorial ambition"? What has become of the assurance "We don't want Czechs in the Reich"? What regard had been paid here to that principle of self-determination on which Herr Hitler argued so vehemently with me at Berchtesgaden when he was asking for the severance of Sudetenland from Czecho-Slovakia and its inclusion in the German Reich?

Now we are told that this seizure of territory has been necessitated by disturbances in Czecho-Slovakia. We are told that the proclamation of this new German Protectorate against the will of its inhabitants has been rendered inevitable by disorders which threatened the peace and security of her mighty neighbour. If there were disorders, were they not fomented from without? And can anybody outside Germany take seriously the idea that they could be a danger to that great country, that they could provide any justification for what has happened?

Does not the question inevitably arise in our minds, if it is so easy to discover good reasons for ignoring assurances so solemnly and so repeatedly given, what reliance can be placed upon any other assurances that come from the same source?

There is another set of questions which almost inevitably must occur in our minds and to the minds of others, perhaps even in Germany herself. Germany, under her present regime, has sprung a series of unpleasant surprises upon the world. The Rhineland, the Austrian Anschluss, the severance of Sudetenland-all these things shocked and affronted public opinion throughout the world. Yet, however much we might take exception to the methods which were adopted in each of those cases, there was something to be said, whether on account of racial affinity or of just claims too long resisted-there was something to be said for the necessity of a change in the existing situation.

But the events which have taken place this week in complete disregard of the principles laid down by the German Government itself seem to fall into a different category, and they must cause us all to be asking ourselves: "Is this the end of an old adventure, or is it the beginning of a new?"

"Is this the last attack upon a small State, or is it to be followed by others? Is this, in fact, a step in the direction of an attempt to dominate the world by force?"

Those are grave and serious questions. I am not going to answer them to-night. But I am sure they will require the grave and serious consideration not only of Germany's neighbours, but of others, perhaps even beyond the confines of Europe. Already there are indications that the process has begun, and it is obvious that it is likely now to be speeded up.

We ourselves will naturally turn first to our partners in the British Commonwealth of Nations and to France, to whom we are so closely bound, and I have no doubt that others, too, knowing that we are not disinterested in what goes on in South-Eastern Europe, will wish to have our counsel and advice.

In our own country we must all review the position with that sense of responsibility which its gravity demands. Nothing must be excluded from that review which bears upon the national safety. Every aspect of our national life must be looked at again from that angle. The Government, as always, must bear the main responsibility, but I know that all individuals will wish to review their own position, too, and to consider again if they have done all they can to offer their service to the State.

I do not believe there is anyone who will question my sincerity when I say there is hardly anything I would not sacrifice for peace. But there is one thing that I must except, and that is the liberty that we have enjoyed for hundreds of years, and which we will never surrender. That I, of all men, should feel called upon to make such a declaration-that is the measure of the extent to which these events have shattered the confidence which was just beginning to show its head and which, if it had been allowed to grow, might have made this year memorable for the return of all Europe to sanity and stability.

It is only six weeks ago that I was speaking in this city, and that I alluded to rumours and suspicions which I said ought to be swept away. I pointed out that any demand to dominate the world by force was one which the democracies must resist, and I added that I could not believe that such a challenge was intended, because no Government with the interests of its own people at heart could expose them for such a claim to the horrors of world war.

And, indeed, with the lessons of history for all to read, it seems incredible that we should see such a challenge. I feel bound to repeat that, while I am not prepared to engage this country by new unspecified commitments operating under conditions which cannot now be foreseen, yet no greater mistake could be made than to suppose that, because it believes war to be a senseless and cruel thing, this nation has so lost its fibre that it will not take part to the utmost of its power in resisting such a challenge if it ever were made. For that declaration I am convinced that I have not merely the support, the sympathy, the confidence of my fellow-countrymen and countrywomen, but I shall have also the approval of the whole British Empire and of all other nations who value peace, indeed, but who value freedom even more.

No. 10.

Speech by the Secretary of State for Foreign Affairs in the House of Lords on March 20, 1939.

IT is quite true, as both the noble Lord who spoke first and the noble Marquess have said, that recent events have been a profound shock to all thinking people in this country and very far outside it. It may perhaps be of use if with all brevity I give the House a short narrative in order to make sure we have the setting correct of what has actually passed during the last few days. The German military occupation of Bohemia and Moravia began on the morning of the 15th March, and was completed, as we know, without serious incident. It is to be observed-and the fact is surely not without significance-that the towns of Mährisch-Ostrau and Vitkovice were actually occupied by German S.S. detachments on the evening of the 14th March, while the President and the Foreign Minister of Czecho-Slovakia were still on their way to Berlin and before any discussion had taken place. On the 16th March Herr Hitler issued the decree, to which the noble Marquess has just referred, proclaiming that the former Czecho-Slovak territory occupied by German troops belonged henceforth to the German Reich and came under its protection under the title of "The Protectorate of Bohemia and Moravia."

It is not necessary to recapitulate the terms of that decree-it has been published-but it should be noted that, while the head of the Administration now to be set up is said to hold the rank of Head of State, and while the protectorate is said to be autonomous and self-administering, a Reich protector is resident in Prague with full powers of veto on legislation. Foreign affairs and the protection of nationals abroad devolve on the German Government, which will also maintain military garrisons and establishments in the protectorate. The protectorate is, further, in the German Customs Union, and, finally, the German Government can issue decrees valid in the protectorate and take any measures for the preservation of security and order. Perhaps I might quote one short article which seems to me to sum up the situation. It says:-

"The Protectorate of Bohemia and Moravia shall exercise its sovereign rights in consonance with the political, military and economic importance of the Reich."

As to Slovakia, the independence of Slovakia was proclaimed on the 14th March, but at the request of Dr. Tiso, the head of the Slovak State, Herr Hitler has undertaken to place Slovakia under German protection and the military occupation of the territory by German troops is now proceeding. As regards Ruthenia, the occupation of Ruthenia by Hungary, which began on the 14th March, has also proceeded. By the 16th March the Hungarian troops had reached the Polish frontier and had virtually completed the occupation of the province. Therefore, as a result of these several actions, the dismemberment of Czecho-Slovakia may be said now to be complete.

Before I come to some one or two of the things that fell from the noble Lord who moved, I would like to say something as to the grounds on which the German Government seek to justify the action that they have taken. The immediate cause of the present crisis in Central Europe originated in Slovakia, and it is claimed that the German Government was entitled to intervene on receiving the request for assistance from the dismissed Slovak Prime Minister. As your Lordships are well aware, there has always been a party in Slovakia which advocated autonomy. That autonomy was, in fact, achieved after Munich in agreement between the various Slovak parties and the Central Government in Prague. The extremist elements in Slovakia, however, were not satisfied with these arrangements, but on all the evidence that is available to me I find it impossible to believe that the sudden decision of certain Slovak leaders to break off from Prague, which was followed so closely by their appeal for protection to the German Reich, was reached independently of outside influence.

It is said that German intervention in Czecho-Slovakia was justified owing to the oppression of the German minority by the Czechs. But, as a matter of fact again it was only very shortly before Herr Hitler's ultimatum to the Czech President that the German press began to renew its campaign of last summer about the alleged Czech brutalities against German citizens Actually the position of the German minority, which is about 250,000, would appear, since the Munich Agreement, to have been one of what might be termed exceptional privilege. Notwithstanding the right of option which had been accorded by article 7 of that agreement, the members of the German minority were encouraged to remain in Czecho-Slovakia in order that they might form useful centres of German activity and propaganda; and advice to that effect was given to the minority by its leader.

It was as a result of the German-Czecho-Slovak Agreement for the mutual protection of minorities that the German Government obtained the legal right to take a direct interest in the treatment of their minority in Czecho-Slovakia. That minority at once obtained the right to set up separate organisations, and the Czecho-Slovak Government subsequently agreed that the German National Socialist Party in Czecho-Slovakia should be given full liberty to pursue its activities in Bohemia and Moravia. It is difficult to avoid the conclusion that the bulk of the incidents which occurred before the German invasion were deliberately provoked and that the effects were greatly magnified. It must be added in fairness that the Czecho-Slovak authorities received orders to act, and did act, with great restraint in the fact of that provocation. It is not necessary, I think, to say much upon the assertion that the Czecho-Slovak President really assented to the subjugation of his people. In view of the circumstances in which he came to Berlin, and of the occupation of Czech territory which had already taken place, I think most sensible people must conclude that there was little pretence of negotiation, and that it is more probable that the Czech representatives were presented with an ultimatum under the threat of violence, and that they capitulated in order to save their people from the horrors of a swift and destructive aerial bombardment.

Finally, it is said that Germany was in some danger from Czecho-Slovakia. But surely the German Government itself can hardly have expected that that contention could be seriously entertained in any quarter. Indeed, if I may sum up my own thought on these various explorations, I could wish that, instead of the communications and explanations which have been issued and which carry scant conviction, German superior force had been frankly acknowledged as the supreme arbiter that in fact it was.

In these circumstances, as you are aware, His Majesty's Government thought fit at once to take certain action. Here I touch a point which was touched both by the noble Lord who moved and by the noble Marquess who followed him. His Majesty's Government immediately suspended the visit of the President of the Board of Trade and the Secretary of the Department of Overseas Trade to Berlin, by means of which it had been hoped that His Majesty's Government could directly intervene in those unofficial contacts of industrial representatives which were at that very moment taking place. We felt, and feel, as I think I said in my statement a few days ago, that in the circumstances which have arisen any development of our efforts in that direction was, as the noble Marquess said, frankly out of the question, and that that and many other things had to be and must remain indefinitely postponed. His Majesty's Government, as your Lordships also know, have recalled to report His Majesty's Ambassador in Berlin, and he reached this country yesterday.

Further than those two practical steps, we have lodged a formal protest with the German Government in the sense of informing them that we cannot but regard the events of the last few days as a complete repudiation of the Munich Agreement and a denial of the spirit in which the negotiators of that agreement bound themselves to co-operate for a peaceful settlement. We have also taken occasion to protest against the changes effected in Czecho-Slovakia by German military action, and have said that, in our view, those changes are devoid of any basis of legality. I think, therefore, that we may claim to have left the German Government in no doubt of the attitude of His Majesty's Government, and although I do not cherish any exaggerated hopes of what may be the effect of protests, I think your Lordships will feel it abundantly right that such protests should be registered.

I have from time to time seen efforts made by German apologists to justify the action of their Government by some reference to the past history of the British Empire. It is not necessary to remind you that the principle on which the British Empire is conducted is education in self-government. Wherever we have been in the world, we have left a trail of freedom and of self-government, and our record has nothing in common with the suppression of liberty and independence of people whose political developments had already brought them to the point of enjoyment of those opportunities for self-expression. It has also been objected that what has happened in Czecho-Slovakia is of no interest or concern to this country. It is quite true that we have always recognised that, for reasons of geography, if for no other, Germany must from some points of view be more interested in Czecho-Slovakia or South-Eastern Europe than we are ourselves. It was the natural field for the expansion of German trade. But apart from the fact that changes in any part of Europe produce profound effects elsewhere, the position is entirely changed when we are confronted with the arbitrary suppression of an independent sovereign State by force, and by the violation of what I must regard as the elementary rules of international conduct.

It is natural enough that in the light of these events His Majesty's Government should be told, as the noble Lord told them this afternoon, that the policy of Munich was a tragic mistake. I cannot, of course, claim to correct the noble Lord upon an expression of opinion which he sincerely holds, but I can correct him, I think, on one limited observation that fell from him. He referred to the policy pursued by the Prime Minister as a personal policy. If by that he means that it was a policy to which the Prime Minister had given every ounce of energy, imagination and resolution that he possessed, I should not disagree with him, but if he suggests that it was a policy that was pursued without the fullest co-operation of myself as Foreign Secretary, and of every member of His Majesty's Government, then I must take leave to oppose to what he said the most emphatic contradiction.

My Lords, the Munich Settlement, which was approved by this House and in another place, was accepted by His Majesty's Government for two purposes, quite distinct. The first purpose was to effect a settlement, as fair as might be in all the extremely difficult circumstances of that time, of a problem which was a real one, and of which the treatment was an urgent necessity if the peace of Europe was to be preserved. As to that, I would say, as I have said before in this House, that I have no doubt whatever that His Majesty's Government were right, in the light of all the information available to them, to take the course they did. The second purpose of Munich was to build a Europe more secure, upon the basis of freely accepted consultation as the means by which all future differences might be adjusted; and that long-term purpose, my Lords, has been, as we have come to observe, disastrously belied by events. We are charged with having too readily believed the assurances which were given by Herr Hitler-that after Munich he had no further territorial ambitions, and no desire to incorporate non-German elements in the Reich. The noble Lord referred to the Prime Minister as the "too-simple Prime Minister." I can assure your Lordships that neither the Prime Minister nor I, myself, nor any member of His Majesty's Government, has failed at any moment to be acutely conscious of the difference between beliefs and hope. It was surely legitimate and right to have hopes. But we have always acted-and I challenge any noble Lord to produce any evidence to the contrary-in the knowledge that only with time can hope be converted into sure beliefs.