Slave to the Game

Online Gaming Community

ALL WORLD WARS

OPERATION CROSSROADS

A Message from the Commander Joint Task Force One

Vice Admiral Blandy

THIS pictorial record of Operation CROSSROADS must be dedicated to the 42,000 men—civilians and servicemen, who made the gigantic experiment possible. It is the record of a job well done. It is a record which makes' impressively clear the extent of the preparations made over a period of months. The variety of activities constituting Joint Task Force ONE is also evident. The Operation called for a multitude of skills and talents. And from every man it demanded hard work. All this is apparent from the record.

From the standpoint of the general public, Operation CROSSROADS constitutes a further example of the type of cooperation between the services—the Navy, Army Air Forces, Army Ground Forces, and civilian scientists and technicians, to which the people of the United States became accustomed during the recent war.

For obvious reasons these photographs no more than hint at the tremendous amount of data obtained concerning the effect of the bombs upon ships and material. They necessarily slight the technical and scientific lessons learned at Bikini. They do, however, evidence an incontestable truth. The Atomic Age is here. It is no myth. Nor is the atomic bomb "just another weapon." It is the most lethal destructive agent yet devised by man. Its energy release is staggering; its radioactivity is slow-killing poison.

The purpose of these tests was to determine the effect of the atom bomb against various types of naval vessels. With the information secured, we can improve our ship design, tactics, and strategy, to minimize our losses in the unfortunate event of war waged with atomic weapons. A reliable and continuously effective plan to avoid competition in atomic armaments is the best possible defense against surprise attacks. With such a plan, atomic energy can in time become the controlled slave of man's peacetime pursuits. In the face of this new knowledge, these recently discovered truths concerning the atom, so suddenly thrust upon an already chaotic world, not only warfare but civilization itself literally stands at the Crossroads. Hence the name of this operation.

Vice Admiral W. H. P. Blandy, Commander of the Joint Task Force ONE

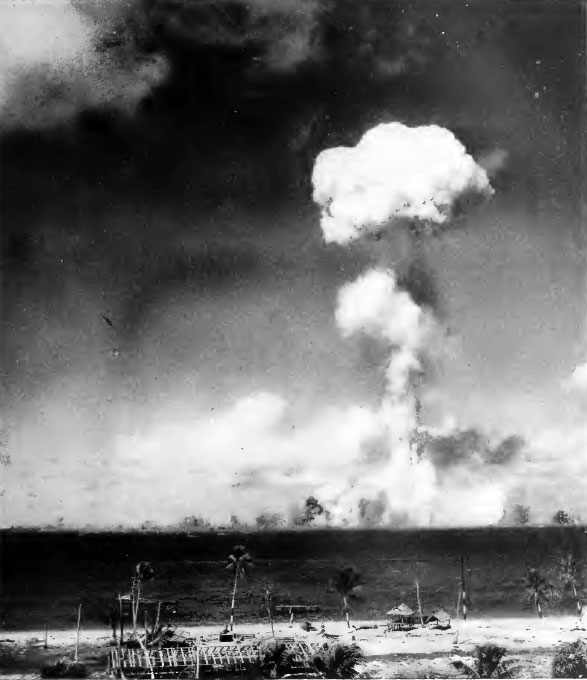

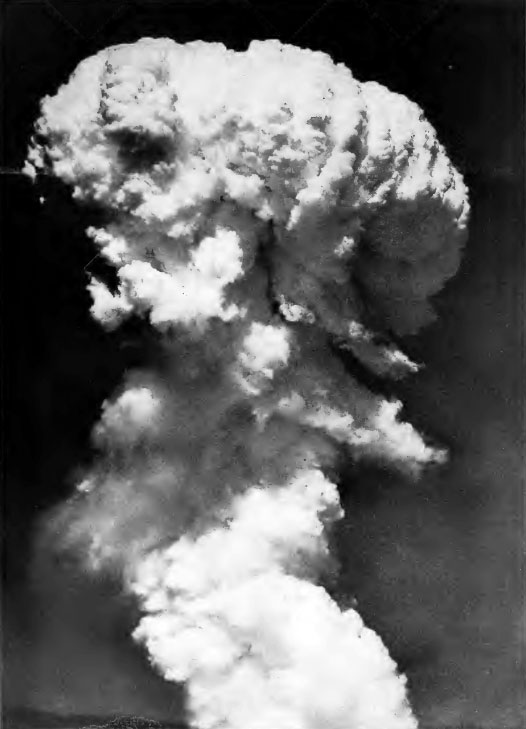

No man really saw what happened at Bikini. Approximately 42,000 persons, drawn from the four corners of the globe, traveled thousands of miles to stage and witness the tests. But an atomic bomb defies scrutiny. It shuns publicity. It shields its intense life-span in a flash of light many times the brilliance of the sun. It dazzles human eyes. It limits its life to a matter of millionths of a second. It enshrouds itself in a cloud. And then it dies, mushrooming grotesquely to high altitudes as if for a better view of the havoc it has produced.

Even if pent up beneath the surface of a Lagoon it resists observation. Where before it blinded the eye here it succeeds in blinding the mind. In a matter of seconds it tosses up a column of tons of water higher than the Empire State Building. It sinks ships in a moment and crushes others into the deformed, stepped-on shape of a child's bath-tub toy. Itself the result of man's intellect, the bomb defies examination by its creator.

And yet the Bikini tests were thoroughly observed. Supplementing human onlookers were 10,000 instruments, and among them cameras, constructed to record what the human eye could never see. Cameras are inquisitive instruments with long memories. In the field of atomic research they are indeed star witnesses. Their story may appear differently to the scientist and the layman. But all may grasp its general significance.

For those who attended the tests these photographs may serve as the lasting momento of a unique experience. For those who did not they should serve to provide perspective concerning the atomic bomb, and give better knowledge of one of the largest scale ventures in experiment ever attempted by man. This foreword has been written with that end in view, and to place Operation CROSSROADS properly in the history of the bomb.

Previous Bombs PRIOR to July 1946 three atomic bombs had been detonated—one above the New Mexico desert, two more above the Japanese cities of Hiroshima and Nagasaki. For an already weakening Japan these bombs spelled defeat. The bombing of Hiroshima, on August 5, 1945 (Greenwich Mean Time) constituted the first military use of the bomb. Nagasaki was hit on August 9 (G.M.T.). On August 14, only nine days after Hiroshima, Japan surrendered unconditionally.

Now it could be told . . . the "best-kept secret of the war," the story of secret research in the field of nuclear physics, the successful tapping of the tremendous energy of the atom, the mass production of materials to make use of this energy in the form of a bomb. The perplexing language of science dominated the columns of the daily press. Laymen throughout the United States scratched their heads and attempted to understand.

One thing was clear. The bomb constituted a revolution in pre-existing concepts of tactics and strategy. The tremendous striking power of the single, unaccompanied bomber over Japan, taken to be a reconnaissance weather plane by those on the ground, was retold with each succeeding bulletin describing the doomed cities. But just how much of a revolution did the bomb represent? No one knew the answer to that question.

Trinity Test

It was true that Bomb Number One, the first atomic bomb ever detonated by man, had been exploded "under laboratory conditions." This was the so-called Trinity Test, conducted in the great, roofless laboratory of the New Mexico desert near Alamogordo on July 16, 1945. The Trinity Test had been observed by scientists, military observers and by hastily-set up instruments. But the instrumentation was meager. The test was carried out during wartime with emphasis on secrecy and the rapid development of a bomb for use in bringing to an end a war that had already cost the lives of millions. Alamogordo represented a proving ground, not an elaborately instrumented experiment. As a source of scientific data concerning the bomb it left much to be desired.

The subsequent uses of the bomb at Hiroshima and Nagasaki were carried out under combat conditions. They, too, were of little significance from a technical point of view. They did provide data concerning the effect of the bomb on a city of the Japanese type; but this data was entirely in the form of rough estimates proving little.

Bomb vs Ships

To many this question arose: What effect would an atomic bomb have on a fleet of naval vessels? Much thought had been given to this question during the development phases of the bomb. As early as 1944 the Manhattan Engineer District, charged with development of the bomb, had given serious consideration to the possibility of ' testing" one of its atomic bombs against the Japanese Navy at Truk Island. And just after the surrender of Japan Senator Brian McMahon of Connecticut made a speech in the Senate in which he advocated the use of the atomic bomb against the captured Japanese fleet.

Speculation on this subject followed diverse lines. What amount and type of damage would the bombs produce in the first instance? To what extent should accepted principles of ship design be altered in future construction? What defensive measures could be taken by a ship attacked with atomic missiles? Were traditional tacical practices outmoded?

Joint Task Force ONE

To answer questions like these the Joint Chiefs ' of Staff, with Presidential approval obtained on January 10, 1946, created Joint Task Force ONE; its mission: to carry out the atomic bombing of a target array of naval ships. Vice Admiral W. H. P. Blandy was designated Commander. This Task Force comprised a total of more than 200 ships, 42,000 men, and 150 aircraft. It included members of the Navy, Army Air and Ground Forces, and civilian scientists. Its directive ordered one test of the bomb in air above the target fleet, and a second detonation in the water, slightly below the surface.

Two tests were necessary. The air and subsurface bursts constituted quite different test situations. This difference can be quickly told. When exploded in air at low altitude, as in Test "Able," an atomic bomb subjects everything in its vicinity to violent air-blast and intense radioactivity. Much of the radioactivity is dissipated into the upper atmosphere in the so-called "mushroom cloud." Ships subjected to the bomb were expected to receive, and did receive a severe air blast or concussion. Crews on the test ships, had there been any, would undoubtedly have suffered many casualties from the lethal radioactivity.

Test "Baker," the underwater shot, utilized the bomb's tremendous energy release in a different way. The huge pressure built up by the bomb under the water was transmitted to the underwater portions of the neighboring ships. Ship hulls were by this pressure forced inward on all sides at once. Furthermore, since the bomb was submerged in the Lagoon, its radioactivity was prevented from passing instantly into the upper atmosphere. Intense and lasting radioactivity was produced in the water of the Lagoon. The ships, drenched by tons of water thrown up by the explosion, became similarly contaminated. The extent of such contamination Droved a matter of great interest.

Bikini

THE Bikini Atoll, a typical Pacific Ocean island group in the Marshalls, was chosen as the site of the test. It is 2000 miles southwest of Hawaii, and 4150 miles from San Francisco. Several factors made Bikini an excellent choice. Its size was ideal—an atoll of several small islands surrounding a Lagoon 20 miles long-and 10 miles wide. Average depth of water inside the Lagoon was approximately 200 feet, a good anchorage for the target ships. The Atoll is remote from fishing areas, steamer lanes. It is located 250 miles north of Kwajalein, a suitable base from which the bombing plane could operate. Its weather conditions were excellent.

Preparations

Plans for the Operation went forward during the Spring and early summer of 1946. Surveys of the Bikini Lagoon were made, its waters combed for truant Japanese mines, its natives evacuated to another island. The islands were sprayed with DDT to insure healthful conditions for Task Force personnel. Towers to house cameras and television apparatus were built. At Kwajalein the available airfield installations were readied for the arrival of the Air Group. Laboratories for chemical analysis and photograph processing were constructed. Little by little the ships of the target array assembled and were brought to Bikini, most of them through Pearl Harbor, which hummed with activity. Installations of special equipment had to be made on many vessels. Salvageable ship materiel was removed. Army equipment scheduled to be secured to the decks of the target ships and exposed to the bomb's destructive force was placed aboard. The German cruiser "Prinz Eugen" moved from European waters to Philadelphia and on to the Pacific. From Japan steamed the captured Japanese battleship "Nagato" and the light cruiser "Sakawa." Also to their rendezvous with destiny came the valiant old battleship "Pennsylvania," commissioned in 1916 and once flagship of the United States Fleet, the 30-year-old veteran "Nevada," first of the Navy's oil-burning super-dreadnaughts, the rugged carriers "Saratoga" and "Independence”.

Several plans for the arrangement of the target fleet were considered and revised. The directive creating the Operation specified a disposition of ships to give a graduation of damage from maximum to minimum. Major damage to ships close to the explosion point, minor damage to ships at the outskirts of the target circle, would provide valuable means of analyzing the bomb's elusive fury. The final disposition appears schematically at a later place n this book. The concentration of ships, from a Navy point of view, was obviously artificial. More than 20 ships were compressed within 1000 yards of the bulls-eye ship. Ordinarily such an area would be used to contain but a single capital ship in a carrier force at sea, or three capital ships in a normal anchorage. The principle of using an arrangement that would provide graduated damage, instead of one representing a tactical formation or anchorage, was followed in both tests.

Instrumentation

The instrumentation program at Bikini constituted the heart of the Operation. More than 10,000 instruments were placed about on target ships, in shore and observer ship and aircraft installations. Simple and complex, the instruments included many that were familiar long before Bikini, many developed specifically for these tests. Various staff divisions under the Technical Director concentrated on apparatus. Their names hint at the breadth of scientific observation planned: bomb operation; pressure and shock; wave motion and oceanography; electromagnetic propagation and electronics; radiological safety; radiation; radiometry; technical photography.

The ships themselves were in a real sense instruments, their recorded behavior in the face of the explosions revealing much of the nature and development of the gigantic forces produced. Ingenious instruments on the ships measured roll and pitch, recorded strain experienced by plates and ribs, wrote down the temperature of ship interiors, tested surrounding air for contaminating radioactivity, radioed their findings to the observer fleet miles outside the Lagoon. Drone, or unmanned, radio-controlled boats and planes played an important part. The boats collected samples of the radioactive Lagoon water when it was still too "hot" to handle. Drone planes penetrated where no man could have ventured, flew through the mushroom cloud on photographic missions, sampled its poisonous content, televised to remote onlookers their instrument panel readings for flight analysis.

Cameras at Bikini took more than 50,000 stills and 1,500,000 feet of movie film. One camera, presumably the world's largest aerial camera, used a 48-inch focal length telephoto lens capable of taking a legible photograph of the dial of a wrist watch a quarter of a mile away. One high-speed movie camera operated at the rate of 1000 pictures per second.

Pre-test Training

THE tests required special training of the 42,000 men who serviced the Operation. Procedures were set up for placing the thousands of instruments, for their care and activation, the collection of their data. Underwater photography techniques were developed as an aid in recording the data from sunken ships. The drone plane and boat programs, Army and Navy, greatly advanced the art of radio-control apparatus and its manipulation. The fact that Test Able was but the third atomic bomb ever dropped from a bomber provided the Army Air Forces with an incentive for considerable valuable and much-needed training in a practically untried field. AAF training for Bikini began in January 1946 at Roswell Field, New Mexico. It concerned drone operation and the bombing mission, the crew for which was selected after rigorous competition.

At Pearl Harbor the Navy trained fire-fighting and damage control teams for the exacting work of first re-boarding the target ships after each test. This work was important in saving instruments from destruction from secondary causes following the explosions, and in advancing the time for safe general inspection of the ships. To safeguard personnel from radioactivity, radiological monitors were schooled in the use of Geiger counters, which detect contaminated areas.

As July I, 1946 (Bikini time), the date set for Test Able, drew near—weather permitting— weather forecasters frowned deeper over the inexorable data on their charts, and in the end made a perfect prediction of clear weather suitable for the tests. Much depended upon their accuracy. Drone planes tried their wings over Bikini; and the varied photographic, reconnaissance, and press planes of the Operation plan rehearsed once more the detailed courses they were to follow. On "Queen Day" the dress rehearsal of Test Able was held. Everything went smoothly. Months of training and planning had borne fruit.

The Tests

On July I, 1946 it was the real thing. The conspiracy of men and instruments against the bomb came into the open. Soon after the first test the collection of data began—the reading of the apparatus, the amassment of facts which would take months to appraise. On July 25 Bikini time (July 24 G.M.T.) came Test Baker, with the bomb slightly below the surface of the water in the Lagoon. This time the work of reentry was retarded by the contamination of the water. Ships were washed down and made "Geiger sweet," that is, free from harmful radioactivity. Concerning the atomic bomb, time for bombast had ceased, the time for analysis of results had begun. The photographs that follow make no pretense at providing results and conclusions that are even now being prepared. It is however hoped that they will aid a greater understanding of Operation CROSSROADS and, more important, further the intelligent discussion of the momentous issues it so urgently represents.

Office of the Historian, Operation CROSSROADS.

Washington D. C. I November 1946

OPERATION CROSSROADS

Bikini, village street.

Typical Bikini home with pandan roof.

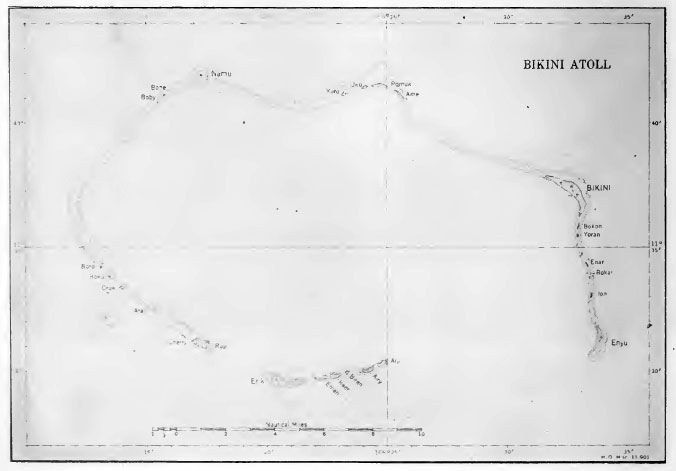

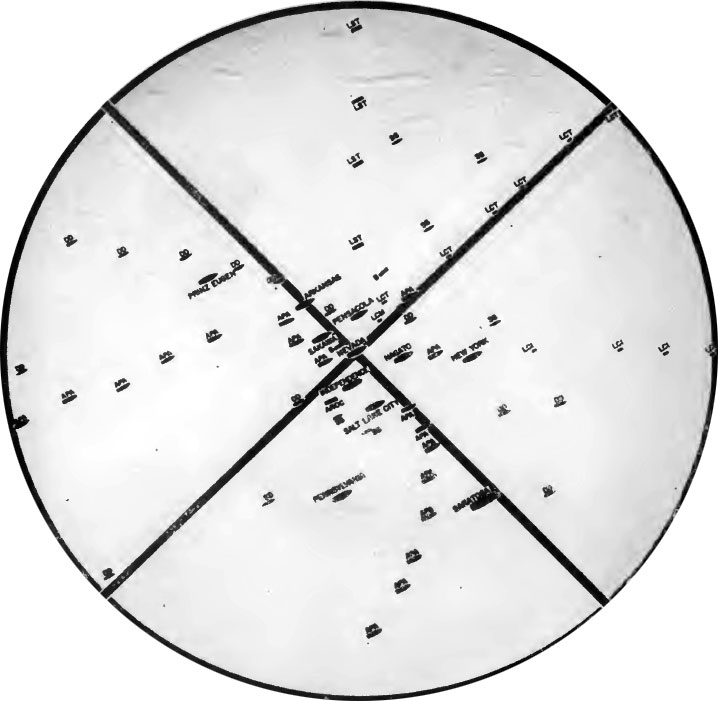

Bikini Atoll map. The target array was located in the northeast part of the Lagoon, about 2 miles southwest of Bikini Island.

Graveyard on Bikini. In February 1946, Bikini residents were evacuated to Rongerik Island, 130 miles east of Bikini.

Young Bikinians.

King of Bikini Juda at Rongerik island, where the Bikinians were evacuated.

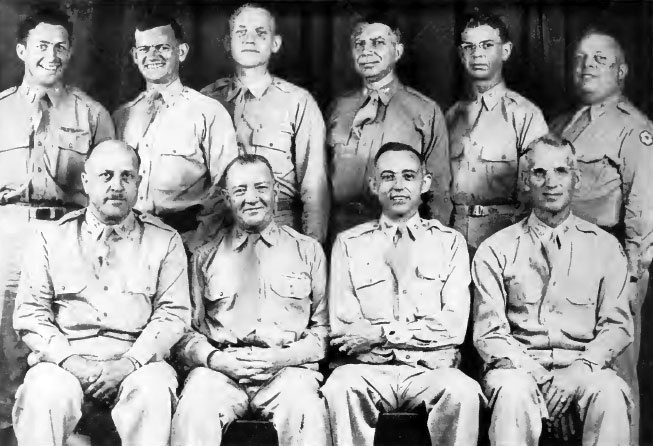

Operation Crossroad weekly staff meeting. Seated, left to right: Major General W. E. Kepner, Deputy Task Force Commander for Aviation; Vice Admiral Blandy, Commander; Rear Admiral W. S. Parsons, Deputy Task Force Commander for Technical Direction; Major General A. C. McAuliffe, Ground Forces Adviser. Rear: Brigadier General T. S. Power, Assistant Deputy Task Force Commander for Aviation; Brigadier General K. P. McNaughton, Captain C. H. Lyman, Assistant Chief of Staff for Operations; Colonel T. J. Betts, Assistant Chief of Staff for Intelligence; Colonel D. H. Blakelock, Assistant Chief of Staff for Logistics; Dr. Ralph A. Sawyer, Technical Director; Captain Robert Brodie Jr., Assistant Chief of Staff for Personnel, and Captain G. M.. Lyon, Safety Adviser.

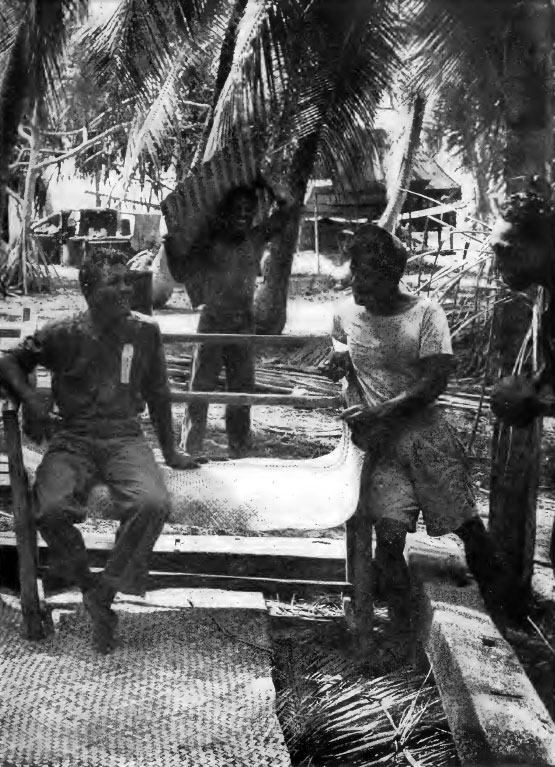

LST 1108 moves outrigger canoes from Bikini to Rongerik.

The Bikinians used sailing canoes were used for hundred miles trips in the open sea.

On March 7, 1946, the population of Bikini was moved to Rongerik in LST 1108, a total of 161 persons making the trip. Seabees and Marshallese at work installing temporary canvas roofs on the new houses. Later, thatch replaced the canvas.

The Bikini church and community house were dismantled and transported to Rongerik.

The dynamite charges were used to remove coral heads from the Lagoon.

One of the completed houses built on Rongerik for the evacuated Bikinians.

In preparation for the Bikini tests a number of scale model experiments were conducted at the Taylor Model Basin near Washington D. C. to aid in estimating the size and character of waves that would be produced by the actual atomic bomb explosions.

Scale charge is detonated.

Various instruments, television, still and motion cameras were installed on top of steel towers erected on various islands surrounding the Bikini Lagoon.

Tower installations on Enyu island. Instruments were used to record the characteristics of the blasts.

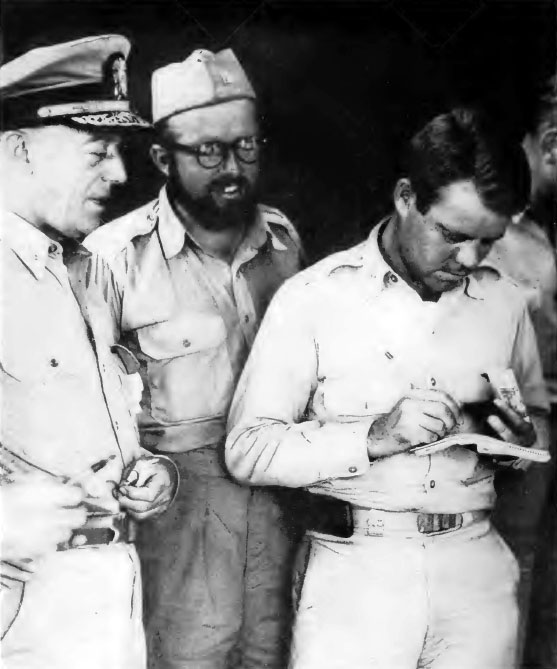

Rear Admiral W. S. Parsons, Deputy Task Force Commander for Technical Direction, clarifies a press conference query at a typical pre-Bikini session in Washington. At the table, left to right: Colonel T. J. Betts, Assistant Chief of Staff for Intelligence; Commodore J. A. Snackenberg, Chief of Staff; Rear Admiral T. A. Solberg, Director of Ship Material; and Dr. R. A. Sawyer, civilian scientist and Technical Director. Extreme right: rear row, Commander Roger Revelle, in charge of oceanographic and wave motion studies. Standing: Colonel Stafford E. Warren, Radiological Safety Adviser, and Lt. Colonel J. A. Derry of the Manhattan Engineer District.

The aircraft carrier "Shangri-La" passes through the Panama Canal en route to Bikini, where she was to join the supporting fleet. The canal locks were so narrow that the ship's barbettes, or side gun platforms, had to be removed to permit passage.

The aircraft carrier "Shangri-La" sails to Bikini. At Bikini the "Shangri- La" controlled the operation of Navy drone planes.

Admiral Blandy's flagship "Mount McKinley", classified as an amphibious warfare flagship.

Ships of the Task Force assemble at Pearl Harbor en route to Bikini.

The Joint Chiefs of Staff Evaluation Board, shown here in conference with Admiral Blandy, kept in close touch with the Operation even in the early planning phase, and subsequently traveled to Bikini to witness the tests. In the above view, members of the Board examine a model of Bikini Atoll with model target ships in place in the Lagoon. From left to right are: Vice Admiral Blandy; Lt. General Levis H. Brereton, Commanding General, First Air Force; Dr. Karl T. Compton, President, Massachusetts Institute of Technology; Rear Admiral Ralph A. Ofstie, Senior Naval Member, Bombing Survey, Naval Analysis Division; Vice Admiral John H. Hoover, Assistant Chief of Naval Operations for Materiel; Maj. General Thomas F. Farrell, USA (Ret.), former Deputy Commander, Manhattan Engineer District; and the late General Joseph W. Stilwell, until his death Commanding General, Sixth Army.

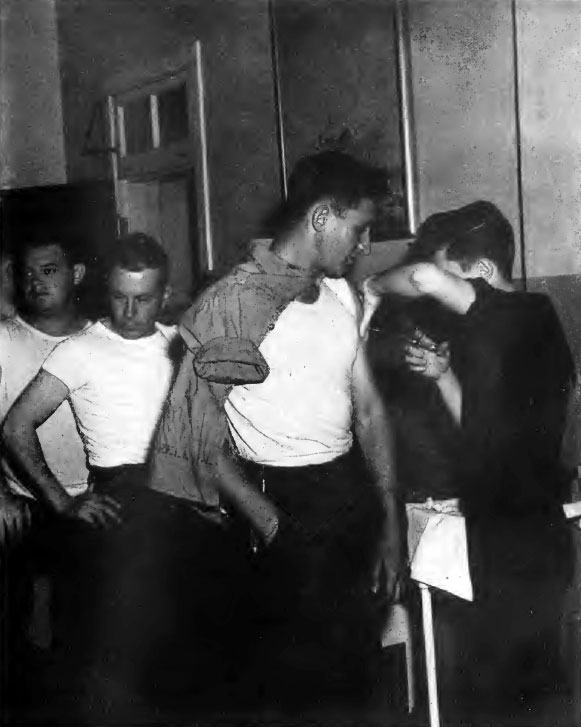

All personnel going to Bikini had to be inoculated for typhus, typhoid, and tetanus, and vaccinated for smallpox.

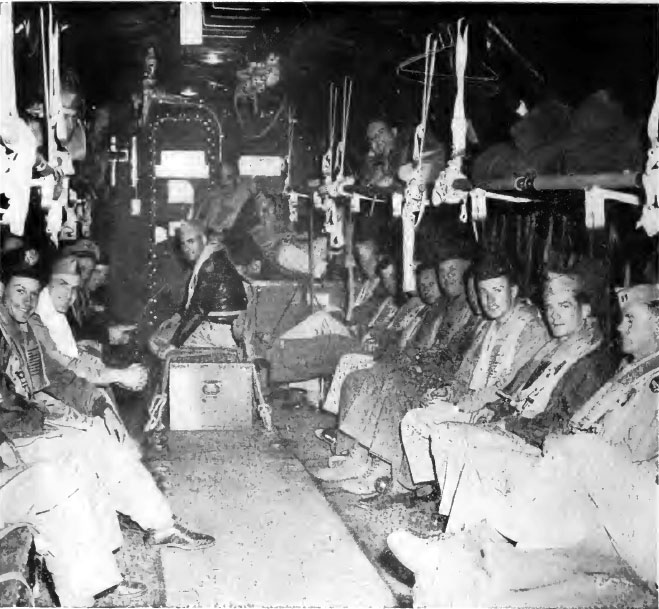

Interior view of a big Douglas C-54 plane of the so-called "Green Hornet" line used to transport personnel and freight from the United States to Kwajalein, 250 miles from Bikini.

Ten Representatives and four Senators journeyed to Bikini to view the atomic bomb tests. Senators and Congressmen en route to Bikini stand in the shade of the plane waiting to ferry them 7500 miles from the National Airport at Washington, D. C. to the Marshall Islands. Left to right: Senator Guy Cordon of Oregon, Senator Hatch, Senator Saltonstall, Representative Dean M. Gillespie of Colorado, and W. S. Newell, civilian member of the President's Evaluation Commission, all wearing parachute harnesses.

Arial view of the Kwajalein atoll. This tiny Pacific atoll played a significant part in Operation Crossroads. From its airstrip, the atomic bombing plane "Dave's Dream" took off for its mission over Bikini. Visible in the background is the support ship "Albemarle," tied up at the old Japanese concrete dock.

On the beach at Bikini Island, Army Ground Group engineers assemble ponton bridges, temporarily anchored off Enyu and later included in the target vessel array.

The standardized roadway "planks," consisting of hollow aluminum beams each weighing 175 pounds, are quickly lifted into place.

Metal floats used by Navy Construction Battalions were called (arid spelled) "pontoons;" they were used at Amen and Bikini as buoyancy members of portable docks.

At Eniwetok Island, 190 miles west of Bikini, a B-I7 Flying Fortress drone plane with its landing flaps down eases in over the beach to a three-point landing. Landings and take-offs of these huge crewless planes were controlled by transmitters on the ground, here the transmitter is mounted in the jeep shown below the plane.

Amphibious members of the 2,750 Air Corps personnel stationed in the Marshalls bring ashore from a power boat the end of an electrical cable extending under water to the destroyer in the background.

In Washington D. C. Vice Admiral W. H. P. Blandy, Commander JTF-I, and Maj. General W. E. Keener, Deputy Task Force Commander for Aviation (both standing) and Brig. General T. S. Power (kneeling) study a "mock-up" of the air operation planned for Test Able.

Navy pilots piece together overlapping photographs, taken from high altitude, to form a single mosaic of an area, in preparation for similar projects at Bikini.

Target vessels, ships and boats of the supporting fleet in Bikini Lagoon.

Supplies for the 42,000 men of JTF-I .

Newspapermen aboard the press ship "Appalachian” indulge in a game of chess.

Octavius Guzman, Mexican journalist, at the left, plays A. M. Khokhlov, Russian newspaperman. Stephen White, New York Herald Tribune, extreme left, Sam Shaffer of Newsweek, in the rear center, and Don Morris of the Philadelphia Record are watching the game.

The CVE carrier "Saidor" launches an F6F Hellcat, shown here making its turn into the wind, while on the carrier deck handlers spot another plane into a take-off position.

A Navy helicopter idly approaches CVE carrier "Saidor" before making a landing on the forward end of the flight deck.

Rainy morning at Kwajalein. The drenched B-29 planes and the cloud heavy on the horizon are typical of rainy mornings in this section of the Pacific. Tail-markings on these planes show their particular function as part of Task Group 1.5.

The giant Tridacna, a marine bivalve of the oyster family. They attain weights of as much as 500 pounds.

Army and Navy personnel hit the beach from an LCI water taxi and head for the recreation area and a swim at Bikini.

Officers attached to the Army Ground Force Group.

A group of enlisted men attached to the Army Ground Force Group.

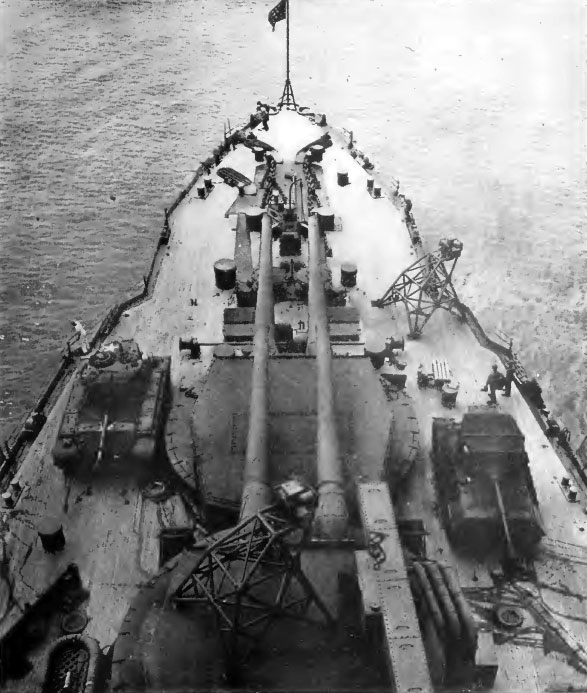

Bow of the battleship "Arkansas" with Army Ground Force equipment in place. A contrast in weapons is presented by the lethal gun of the M-26 heavy tank on the port bow, the 12-inch rifles of the "Arkansas," center, and the Mark 36 90-mm gun mortar carriage on the starboard side of the ship. The rugged supports seen on the starboard deck and on the top of the gun turret, center, are bases for aluminum foil gages, yet to be installed, used to measure shock wave. Ground Forces equipment placed on various target ships for exposure to the explosion included heavy tanks, delicate radar and sound devices, flashproof clothing, fresh and canned rations, fuel and lubricants, numerous kinds of ammunition.

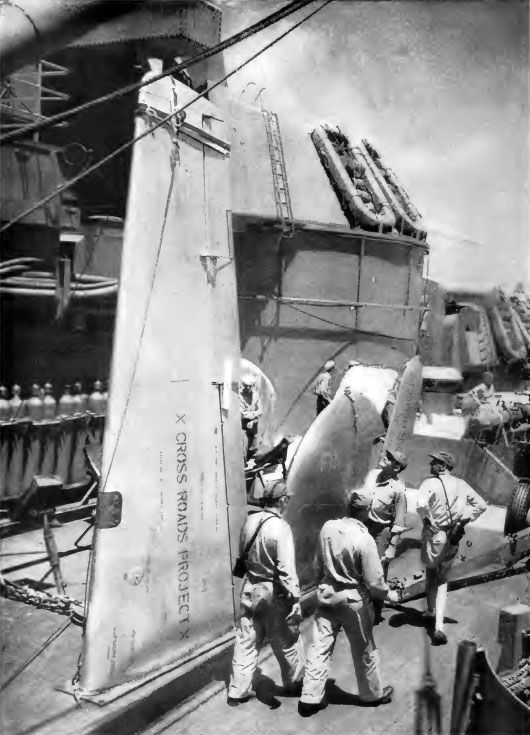

Experimental wing panels installed by Task Group 1.4 personnel on the deck of a target vessel, to find the vulnerability of such panels to atomic bomb explosions. Visible also along the deck are a tail assembly, stabilizer, range-finder, and rear support of a small mobile gun.

Briefing in the well-appointed Operations Room of Task Group 1.5 at Kwajalein was aided by the use of maps and charts painted with fluorescent pigments and irradiated in semi-darkness by ultra-violet light. At the left of the central chart is a simulated radar screen showing what the pilot will see on his own radar screen as his plane approaches its goal. During briefing each B-29, F-13, or C-54 plane's crew occupied a particular row in the center section, seating being according to rank.

Congressman W. G. Andrews (R) from Buffalo, New York, acts as master of ceremonies at a "Happy Hour" aboard the AGC 3 "Panamint," which transported many of the observers to Bikini.

Army nurses stationed at Kwajalein relax with friends. There were 37 nurses in the Task Forces.

On the beach at Bikini men of the Task Force try out the swimming facilities of the recreation area at the south end of the island.

This mass grouping of cameras used by the Army Air Forces to photograph the atomic bomb explosions gives some idea of the extent of the aerial photographic coverage of these tests. Not shown here is navy camera equipment used in planes and on ships, or in fixed shore installations used by various technical groups. The AAF camera roster totaled 328, including aerial motion and still cameras, and among them the world's largest still camera, a giant instrument with a 48-inch focal length telephoto lens. Other unusual cameras included gunsight cameras and ultra high-speed cameras capable of taking 10,000 frames per second under ideal conditions.

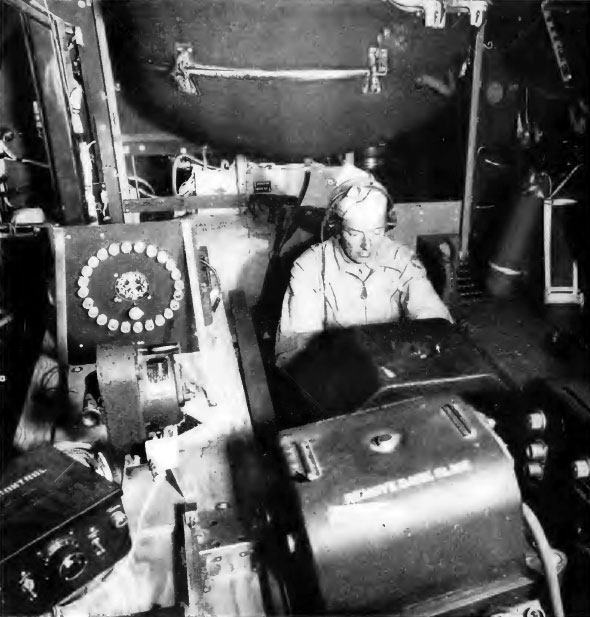

On a Boeinq P-13 plane altered for use as a photographic ship two motion picture cameras are installed in one of the plane’s gun turrets. These cameras were controlled from the top fire control blister shown in the background by the same sighting and firing mechanisms normally used with the plane's machine guns. Shown here at Roswell Field, New Mexico, are Corporal Harold Johnson, outside the plane, making adjustments on the cameras, while Sergeant Henry R. Zarnoski mans the controls in the top fire control blister.

Brigadier General Roger M. Ramey, Commander Task Group 1.5, discusses Army Air Forces photographic plans with Colonel Paul T. Cullen, in charge of technical photography at Kwajalein. In the foreground are i6 and 35mm type motion picture cameras, operated at 2000 frames per second, such as are used in the F-13 photographic ships.

Inside a C-54 photographic plane flying at high altitude, a row of cameramen aim their lenses at the Lagoon below.

At Kwajalein a huge photographic laboratory was built, its atmosphere cooled and dehumidified to prevent damage to film. The bulk of the photo-processing work was done at the U. S. Naval Photographic Science Laboratory at Anacostia, D.C. In the entire operation over 50,000 still films and millions of feet of movie film were exposed.

Scrappy Air Forces boxers battle it out in the humid night air at Kwajalein. On the carrier "Saidor" the airplane elevator, raised to a level three feet above the main hangar deck, served as an improvised ring.

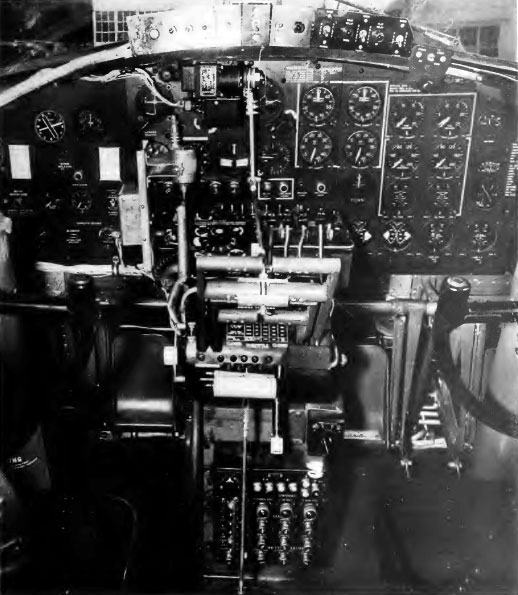

This close-up view of the Plexiglas nose of a B-17 drone plane shows a television camera in the position normally occupied by the bombsight. Shown checking equipment is Captain Renee Dussaq, flight technician. Television relayed what the drone plane "saw" to television receivers miles away; the received images were studied by scientists and recorded on motion picture film. Televised images of the drone's instrument panel helped the remote-control personnel keep the drones flying smoothly.

A battery of heat lamps serves to dry out electronic equipment used at Bikini. High humidity, a principal source of discomfort to men, plays havoc with delicate electronic devices such as those shown.

Technicians prepare panels of fabrics for exposure to the effects of the atomic bombs.

Experts examine pyramidal orientometers on a target ship. These devices indicate the direction from which the heat and radiation from the atomic bomb came, in terms of burns produced when radiation passes through the tiny holes shown and strikes the base of the instrument.

Dr. C. W. Lampson of Princeton University and Captain A. E. Uehlinger, USN inspect an aluminum foil gage.

R. S. Warner Jr., shown at the left was responsible for the assembly and arming of atomic bomb. He had been a central figure in the Bomb Design Section of the Los Alamos Laboratory since 1944 and was the logical choice for Head of the Bomb Operation Group at Bikini. With him are Lt. Colonel R. J. Cunningham, center, and Colonel P. T. Cullen, right. Final preparation of the Test Abie bomb was made by two Navy officer "weaponeers" who flew with the bomb in Dave's Dream. In Test Baker Mr. Warner completed final preparation of the underwater bomb and, with Rear Admiral W. S. Parsons, was among the very last to leave the Zeropoint Ship LSM-60, beneath which the bomb was suspended.

At their San Diego training station Navy carrier-based pilots from the "Saidor" are briefed prior to making practice flights.

Representative ships of the Task Force fleet—three of them target ships and two of them supporting ships. Japanese cruiser “Sakawa”.

"Pennsylvania," She served the United States for 29 years and was among the ships damaged at Pearl Harbor.

"Appalachian." Served as the press headquarters ship for 169 newspapermen, photographers, commentators, and magazine writers covering Operation Crossroads.

"Panamint." The AGC-13 "Panamint" served as headquarters for congressional, scientific, and United Nations observers.

"Nevada." The battleship "Nevada," bulls-eye ship at Test Able, was painted orange-red to aid the bombardier.

Radio-controlled drone boat prepared for operation.

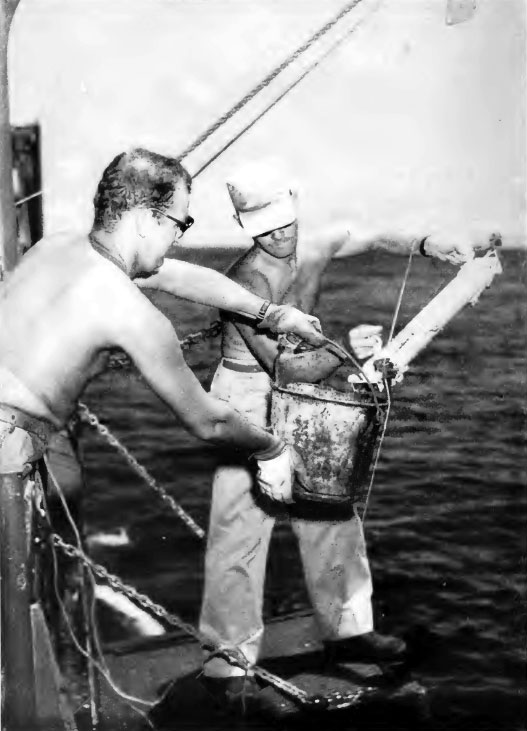

Samples of Laqoon water are taken using a Nansen bottle.

In the Army Air Forces briefing room on Kwajalein Island VIP's, drawn from military, Congressional, and civilian ranks enjoy a ten-minute break in a briefing session. Front row, left to right: General George C. Kenney, Commanding General of the Strategic Air Command; Stuart Symington, Assistant Secretary of War for Air; General Curtis E. LeMay, Deputy Chief of Air Staff for Research and Development. Second row: Colonel Kenneth B. Nichols of the Manhattan Engineer District. Second row, center, Senate Leverett Saltonstall engages in conversation with Postmaster General Robert E. Hannegan, Chapman of the Democratic National Committee.

Coral head in shallow water, showing the boulder-like shape taken by these heavy masses. Blocks of coral like this one, found as far as 400 feet from +he reef edge, are torn from the margin of the reef by storm waves and deposited on the reef flat. The one shown, found 100 feet from the reef edge on Erik Island, was 25 feet in diameter and 12 feet high.

The pause that refreshes, Enyu Island.

As the exacting preparations for the first atomic test approached completion, and as the date of the first explosion drew near, informal pools were organized as to how many ships would be sunk, or as to the exact time when the bomb would actually be detonated. Rear Admiral T. A. Solberg, Director of Ship Material, with N. J. Holter, project physicist for wave measurement, watches Major Harold H. Wood, bombardier of "Daves Drearm." the bomb-drop plane, keep the record on a "minute of detonation" pool. Of 60 possible choices, Holler's paid off.

On Kwajalein an Army Air Forces weather balloon goes aloft.

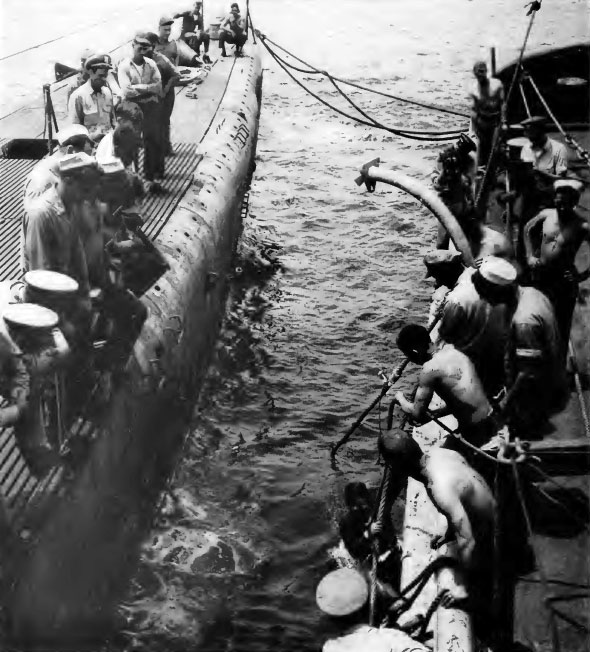

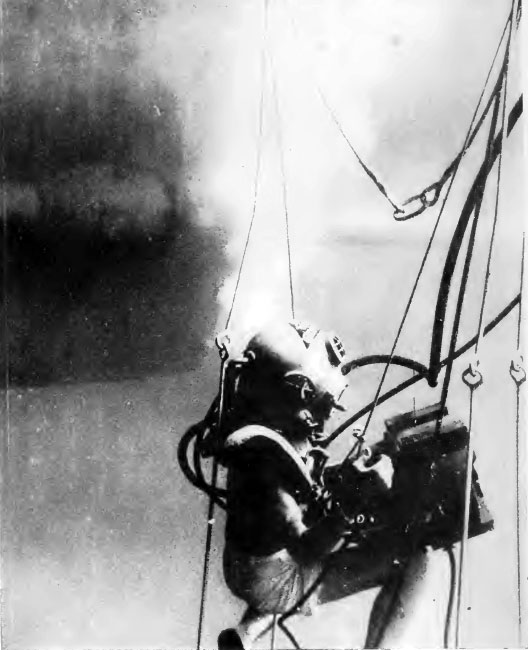

Men of the Navy salvage ship "Reclaimer" hoist a 14-ton anchor over the side. Anchors of this type were used to hold submarines in place during the second atomic bomb test.

A diver from the "Widgeon" goes down to adjust cable attachments on the submarine "Apogon."

Navy diver in light facemask comes up.

The sub "Apogon", surfaced but with underwater control weights in place. Submarines proved to be useful "instruments" for subjection to the enormous pressures created by the atomic bombs, since their hulls are expressly designed to withstand high pressures produced by the ocean at great depths of submergence, and

by exploding depth charges and mines.

The submarine "Apogon" is shown here partly submerged, controlled from the "Widgeon."

This deck view of a typical target ship shows how the test animals were placed for exposure to the atomic bomb explosions. For Test Able 176 goats, 146 pigs, 109 mice, 57 guinea pigs, and 3,030 white rats were used. They were placed on 22 target ships, in positions normally occupied by ship personnel.

Recalcitrant porker finds himself caught in the draft, on USS "Burleson." In addition to effects on fully exposed animals, effects on animals partially shielded from the radiations were studied. It was desired to learn, for example, how deadly the instantaneously produced gamma radiation would be to personnel below decks and in gun turrets. White rats were placed in various sites from the

engine room to halyards to check all locations.

This view of the control panel of a B-17 Flying Fortress drone. The eight drones used, four by Navy and four by Army, made scores of successful flights and flawless landings.

Personnel of the "Pennsylvania" go over the side during the dress rehearsal. Vital to the success of Queen Day was the evacuation on the previous day of the 42,000 men of the Task Force from the target vessels, the Lagoon, and the encircling islands.

Men of the "Pennsylvania" are checked off as they abandon ship. Every man had to be accounted for, including the technicians who had made hurried, last minute adjustments on scientific instruments on target ships and islands.

Gun turret doorway is dogged and marked secure.

View inside one of the C-54 planes converted for use as an Army Air Forces photographic ship. At the left can be seen the equipment used to record time of operation of each one of the plane's 28 still and motion picture cameras. Each tiny light in the circular panel array represented a particular camera installed somewhere in the plane. Each time that camera's shutter clicked tne light on the recording panel flashed on and was recorded by means of a motion picture camera shown just in front of the panel itself. The clock at the center of the circle of indicator lamps was photographed at the same time, completing the accurate record made.

Touring the Bikini Lagoon while in earnest conference with Admiral Blandy are Major General W. E. Kepner (left), Deputy Task Force Commander for Aviation, and Hon. James Forrestal, Secretary of Navy.

Final preparations in the Lagoon. Long before July I, 1946, the date set for Test Able, ships of the target array had been placed in their assigned positions in the northeast part of the Lagoon. In the view shown above several key ships of the target array are visible. At the top, right of center, "Nevada," the bulls-eye ship, is clearly discernible, painted bright orange-red to aid recognition by the bombing plane. Close beside "Nevada," left and right respectively, are the carrier "Independence" and the cruiser "Pensacola." At the extreme left of the array is the carrier "Saratoga," identifiable by her long flight deck and oblong "island."

Bombardier’s view of the target array. This diagram of the Test Able target array, when compared with the two typical tactical arrays pictured on the opposite page, demonstrates the abnormally high concentration of target vessels in the Bikini tests. This concentration was necessary to meet the Joint Chiefs of Staff requirement of securing graded damage on all principal types of

vessels, graded damage meaning damage ranging from negligible, as in the case of ships at a considerable distance from the explosion, to lethal, in the case of ships close in. Subject to this requirement, sinkings were kept to a minimum, to preserve instruments and the valuable data they had recorded, and to save the ships themselves insofar as it might be possible,

Typical harbor anchorage. This diagram, depicting an area identical to that of the target array, shows a typical harbor anchorage of naval vessels, and, by contrast, emphasizes the high degree of concentration of the target ships used at Bikini. In the harbor anchorage only four to eight ships would normally appear in an area of one square mile, instead of 20, as at Bikini. When the test plans were first announced many persons erroneously assumed that the target array selected would be a tactical one. Actually, the array was entirely artificial, and of no tactical validity.

Carrier force at sea. Shown here for further comparison is a diagram of a carrier task force in cruising formation. Only one capital ship is included in an area of one square mile. In studying the target array opposite, note that the various types of vessels were arranged in curved lines radiating from the bullseye ship "Nevada." Each line was composed of ships of a single type, such as APA's, destroyers, LCI's, LST's, or LCT's. The individual ships served as excellent gages for determining how damage to a given type of ship varied with distance from the bomb burst. For Test Baker the arrangement of ships was generally similar to that used for Test Able.

Flight-deck briefing on Saidor. Grouped in front of an F6F-5P photographic plane, pilots of the 'Saidor" planes receive final briefing from Captain J. H. McElroy, Photographic Operations Officer, shown kneeling, center. Looking on are Captain A. P. Storrs, skipper of "Saidor," and Commander J. H. McCurtin, Air Officer.

Forecast for Bikini and vicinity. Major Delmar L. Crowson, left, officer in charge of the Crossroads Weather Central, Kwajalein, and Major Paul L. Fackler, right, of the Army Air Forces weather group, plot reconnaissance "tracks" or courses to be followed by weather planes in their daily flights out over the Pacific prior to Test Able.

Dave’s Dream on the bombing run. This photograph of "Dave's Dream," taken from an accompanying photographic plane on Able Day, shows the big B-29 on the actual bombing run, her bomb-bay doors open, shortly before the atomic bomb was released at high altitude above the target array.

Officers and men of the carrier "Saidor," assembled on the flight deck, rehearse the safety procedure followed on Able Day to protect their eyes from the blinding light emitted by the explosion.

Early picture of the flash, Test Able.

Airman’s view, Test Able. This picture taken at high altitude, gives the impression that the Test Able bomb was detonated in darkness. Actually the bomb was exploded at nine o'clock in the morning in bright sunshine; the darkness of the photograph is due to the density of filter used.

Clouds, highlighted by the flash. This phototjgraph, like the others in this group, was taken from a distance of about 15 miles from the bomb detonation point.

Light emitted by an atomic bomb covers all portions of the spectrum—light visible to man plus ultraviolet and infrared light.

Condensation cloud formed, test Able.

Condensation cloud, closer view, Test Able. This closer view of the condensation cloud shows ships of the target array silhouetted against the brilliant backdrop that reaches thousands of feet into the air. The vessels visible are those at the edge of the target array.

Progress of the shock waive. In this remarkable photograph the Test Able explosion is shown in another early stage of development. Location of the shock wave is indicated by the flat white ring expanding across the Lagoon's surface from the center of the explosion and its enveloping condensation cloud. This view also gives a good impression of the general relation of the bomb test site to the Bikini Atoll, seen here as a sprawling elliptical chain of islands linked each to each by shallowly submerged reefs. The large island in the foreground is Enyu.

Condensation cloud, tower view. This picture, taken from one of the camera towers on Bikini Island, records a closer impression of what went on inside the Lagoon instants after the Able bomb exploded. Dazzling light from the condensation cloud obscures most of the target ships, although the "Saratoga" is visible at the left of the photograph, and the end of one of the radial lines of evenly spaced smaller craft can be seen. The striped poles and striped marking on palm trees in the foreground were used to measure wave heights at both tests. The long framework building at the edge of the beach is a Marine recreation building. Its tarpaulin roof has been removed to prevent destruction by the shock wave. When this picture was taken the shock wave had not yet hit the beach. Shock wave location is indicated by the sharp bright area near the "Saratoga."

This photograph indicates perhaps better than any other, the dramatic quality and vast scale of the first of the atomic bomb tests. The tethered ships of the target array are dwarfed by the giant white ring, the condensation cloud. The huge fireball at the center is already beginning to make its swift, silent ascent. Reflection of the fireball's brilliance is clearly seen, interrupted by ruffled water whipped b y t h e rapidly expanding shock wave. By the time this picture was taken most of the damage shown on the following pages of this book had been already inflicted.

The curtain rises within the Lagoon. This is one of the earliest views obtained of the target array as it appeared after bombardment. The base of the condensation cloud that previously shielded the ships from the prying eyes of remote and shore-based cameras has disappeared. Its upper portion still remains, hanging over the Lagoon like a thick gray blanket. Smoke from fires started by the bomb can also be seen.

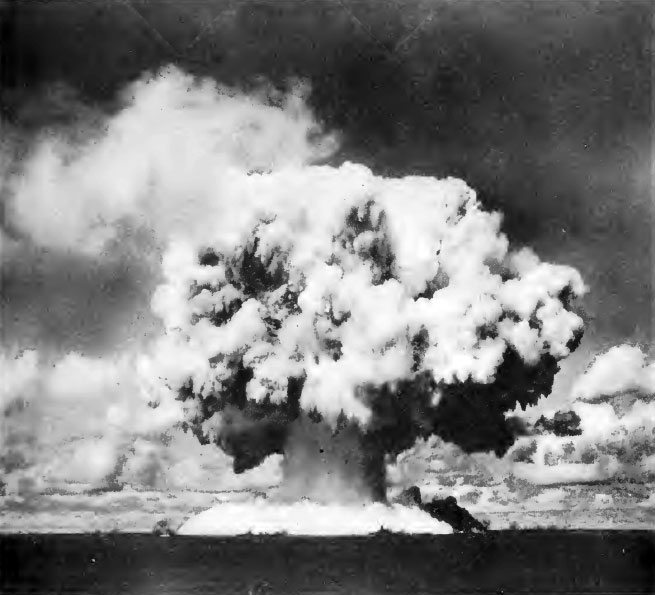

Test Able panorama. This awe-inspiring view of Bikini Lagoon was made instants after the condensation cloud had completely disappeared, revealing the target ships and the turbulent mushroom cloud rising above them. The shock wave from the explosion has not yet had time to cross the Lagoon to the location of the camera, but can be seen as a sharp black line racing towards the beach. A moment later it reached the palm trees at the edge of the water. Slightly to the left of the base of the mushroom can be seen the "Arkansas." The "Nevada," if it were visible, would appear slightly to the left of "Arkansas."

As the mushroom cloud climbs higher into the sky, a second smaller mushroom top appears high on the "stem." The stem itself is composed of a mixture of ascending vapor, steam, spray, smoke, and radioactive fission products. In the vicinity of the stem there is a powerful updraft which sucks inwards and upwards the soot and smoke spouting from the target ships, and spews forth its insidious content into higher altitudes. When this photograph was taken the cloud had risen to about 12,000 feet.

High above Bikini Lagoon an aerial camera caught this impressive view of the Able Test. Note that the shock wave, the circular arc clearly visible on the surface of the water, has just about reached the Atoll islands nearest to the bomb detonation point. In the same space of time the bomb cloud has risen many thousand feet into the sky. Position of the shock wave indicates that all this action has required no more than about five seconds.

In this view the mushroom cloud has risen considerably higher than the altitude indicated in the preceding photograph. The top of the mushroom is beginning to flatten out somewhat; on the under side of the top spurs of vapor have begun to form, extending downwards. The Test Able shot has been described as

a "self-cleansing" shot since the bomb was detonated in the air and the upward column of gases served to remove most of the radioactive fission products from the lower atmosphere.

OPPOSITE. Close-up view of the explosion cloud, which is beginning to slow up somewhat as it approaches the top of its climb. Manned planes had to stay miles away from this seemingly innocent cloud, the radioactivity of which was roughly equivalent to what would exist in the vicinity of 100 tons of radium. Drone planes were flown right through the center.

Enyu island view of the Test Able. From Enyu Island, approximately five miles from the center of the target array, the Able Test mushroom appears in an advanced stage, dramatically illuminated by the clear morning sunshine. The cloud has already drifted appreciably downwind, to the southwest. Among the target ships embroiled in the mushroom base are "Saratoga" and "Nagato," whose outlines are discernible here. Smoke coming from behind the "Saratoga" is from fires on the carrier "Independence."

The bomb cloud photographed by a drone B-17 about to pass right through it.

"Those were dramatic seconds in sheer beauty. The cloud was a pheasant brown with white patches at first. Then it began an amazing transformation in colors and shapes before our eyes. It seemed to steam and boil and churn at the bottom. There it turned laundry white. It was pinkish in the middle, salmon colored at the top. In less than two minutes it climbed higher than the altitude of our ship "The Voice." The mushroom broke out suddenly at the top, and the cloud changed colors. It was a fascinating picture. For a few minutes it looked like a giant ice cream cone as it turned completely white. Looking at it then through binoculars it seemed like floating layers upon layers of whipped cream. Again it changed colors, now to peaches and cream. It broke into two mushrooms, the second quarter of the way from the crest. All this time the trade winds were driving it hard..." (John M. Carlisle. From the Able Day Pool News Report).

Further view, Enyu island. In this later view of the Able Test mushroom the cloud has risen so high that an icecap has begun to form. Gases rising just above the mushroom top are greatly expanded and therefore cooled; their water vapor content changes from gaseous to ice crystal state. A thin layer of myriad horizontal crystals forms slightly above the top surface of the mushrooms proper. This layer becomes increasingly thicker, gradually settling down over the top of the mushroom. Even after the format on of the icecap the mushroom continues to rise.

At Rongerik Island, former Bikini residents in their traditional modest Mother Hubbard smocks crowd forward for a better view of a Test Able photograph.

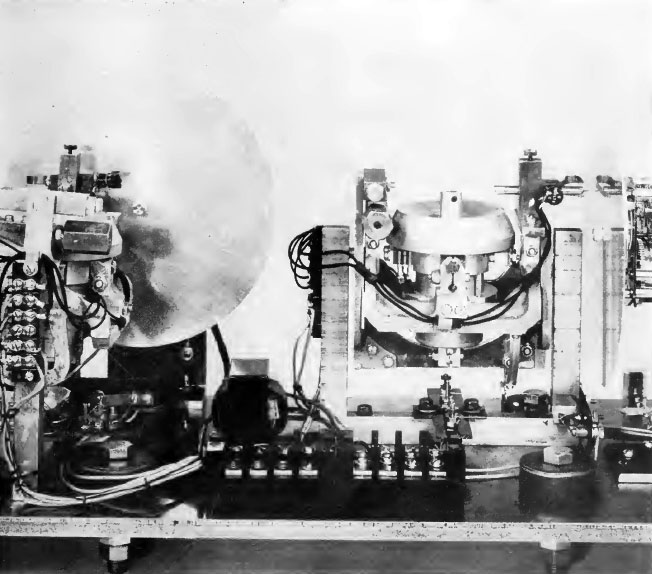

One of the simpler pieces of apparatus used at Bikini was this pendulum-type inclinometer used to measure pitch and roll of target ships. Each instrument contained identical assemblies mounted at right angles as shown. The weighted arm was designed to remain vertical at all times, angle of pitch or roll being measured and recorded as scratches on the shiny discs provided.

Similar in purpose to the pendulum-type inclinometer is this gyroscopic instrument. In this design the standard of verticality is achieved not by a weighted bar but by electrically driven gyroscopes. As in the pendulum-type instrument, two complete units are mounted at right angles, one to measure pitch, the other to measure roll. Both these instruments were developed for the Bikini tests at the Material Laboratory of the New York Naval Ship yard. They are but single examples of the total of 10,000 instruments used to gather important data.

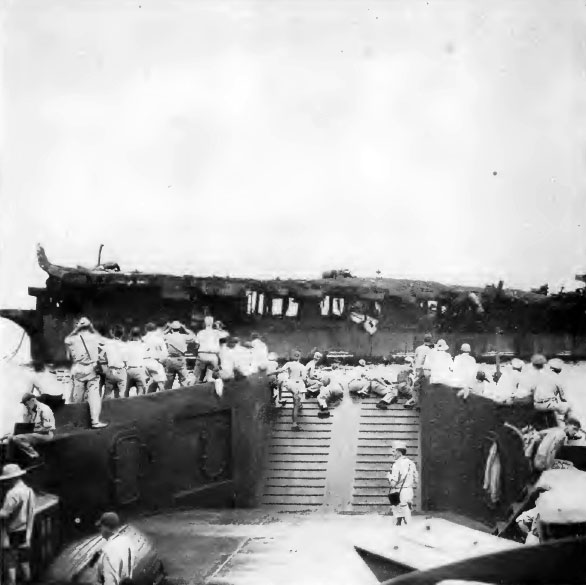

Members of the Joint Chiefs of Staff's Evaluation Board and the President's Evaluation Commission tour the Bikini Lagoon for a first-hand view of damage produced by the Able Day test. Members of the Evaluation Board witnessed the explosion from an airplane 20 miles distant, and later approached to within nine miles for a brief view. The day following, as soon as safety clearance had been received, the Board members began examination of ship damage. In a report made public the Board stated various findings: The only major combatant ships within one-half mile of the bomb explosion point were the battleships "Nevada" and "Arkansas" and the heavy cruiser "Pensacola." Little damage had been done to the hulls or main turrets of these ships but their superstructures had been badly wrecked. There was relatively little damage to ships at distances greater than three-quarters of a mile. The group includes, left to right: Captain Horacio Rivero, Vice Admiral J. H. Hoover, Mr. Bradley Dewey, Dr. Karl T. Compton, the late General J. W. Stilwell, Mr. Fred Searls Jr., Senator Leverett Saltonstall of Massachusetts, Lt. General L. H. Brereton, Dr. E. U. Condon, Representative W. C. Andrews (R) of New York, and Mr. T. F. Farrell.

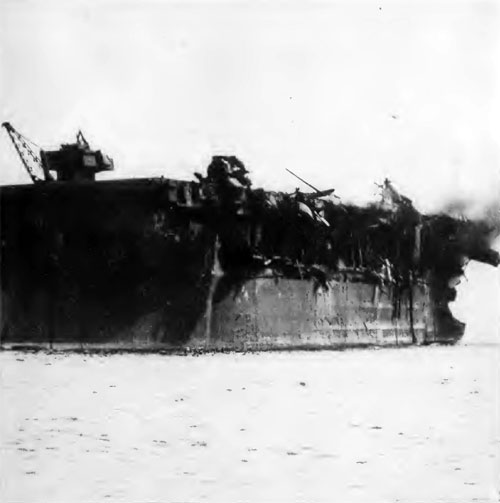

The carrier "Independence" seen by the vanguard of persons reentering the Lagoon following Test Able. The light carrier was badly wrecked by the explosion, gutted by fire, and further damaged by explosions of low order, including those of torpedoes. The Joint Chiefs of Staff's Evaluation Board made a terse statement which was issued to the public from the White House. The bomb, they said, had exploded with an intensity approaching that of the best of the three previous atomic bombs. It had exploded at a point 1500 to 2000 feet westerly of the assigned target, and at approximately the planned altitude. The light carrier "Independence" was within one-half mile of the explosion point.

Blasted portside of the carrier "Independence", her plates molded to her frame by the explosion.

CLOSE IS NEAR ENOUGH. The light carrier "Independence" is a shambles. Visible to the inspecting newspapermen are the combined results of the tremendous pressure wave and intense heat produced by the bomb: the bulged and torn flight deck, charred remains on flight and hangar decks. Invisible are the lingering effects of the bomb's radiation, which even as these pictures were made make the grotesque wreck still too "hot" for more than brief visits. This gutted ship incontestably evidences the great range of effectiveness of the single atomic bomb which had exploded high above the surface of the water, about one-half mile from the doomed ship. Under these circumstances "Independence's" position was virtually a front row seat.

The Japanese cruiser "Sakawa's" superstructure and hull suffered major damage from the bomb explosion. Visible in the photograph above are the mid and stern sections of the ship, a mass of metallic rubble. Invisible are the breaches in her hull below the waterline, due to which she slowly filled with water and sank. Many observers wondered how a mere shock wave in air could wreck such havoc on a steel ship. The situation can be understood with the use of simple arithmetic. According to a well-known law of physics a gas expands by I /273 of its volume (at zero degrees C.) for every degree Centigrade that it rises in temperature. If its temperature rises 273 degrees its volume doubles. But the high temperature instantaneously produced at the heart of the atomic bomb explosion is measured in millions of degrees; the resulting expansion is obviously extremely great. Out of this expansion, so suddenly produced, the overpowering shock wave is born.

The day following Able Day the Japanese cruiser "Sakawa" sinks slowly beneath the water of the Lagoon. In the background is the battleship "Arkansas" which, like "Sakawa,' received major damage to superstructure, although the battleship's hull received little injury.

This ruined two and one-half ton Army truck is on the stern of the bullseye ship "Nevada." The bomb exploded 1500 to 2000 feet west of the ship, and the shockwave struck "Nevada" on her stern quarter. Even at this range the light gage metal of which the truck is built was quickly turned into the crumpled wreck shown. A member of the Army Ground Group checks damage, using forms prepared before the tests to insure thorough reporting of data. In addition "before" and "after" photographs were made of all equipment exposed.

The crumpled remains of a Navy seaplane on the stern of "Nevada" demonstrate further the destructive power of the atomic bomb even at a distance of 1500 to 2000 ft. Collectively such damage data, together with the scientific results obtained from the tests, will prove valuable not only in naval and military engineering but also in many important scientific fields. The results of Operation Crossroads go much further than military questions alone.

On the weather deck of the APA-77 "Crittenden" an FM-2 "Wildcat" airplane is given a thorough examination following Test Able. The plane has a broken fuselage and boat wings as a result of its exposure to the bomb. The effect of shock wave on equipment like this was to some extent influenced by shielding afforded by portions of the ship s structure and by other test material. Concerning personnel, the Evaluation Board stated that casualties due to blast would undoubtedly have been high for those in exposed positions on vessels within one- half mile of the explosion center.

General damage on stern deck, Nevada. Such spectacular damage to equipment exposed on the decks of target ships, in this case Nevada," was produced only in Test Able. The Test Baker damage was primarily in the form of ships sunk by the underwater blast wave, and ships afloat but dangerously contaminated by the huge amounts of radioactively noxious water that had poured down upon them. Nevada's" coat of bright orange-yellow paint, put on to aid the bombardier's aim, was badly scorched by the heat of the explosion.

APA-79 "Dawson" was not very severely hurt by the Test Able explosion, although some damage was suffered, as shown. Her outer stack casing shows a considerable dent, and her radar mast has been pried from its support. On the top of the house, extreme right of the ship, was placed a support for gages used for measuring shock wave pressure.

Use of drone boats as collectors of water samples from Lagoon areas where contamination was great rendered the boats themselves extremely "hot." Like the ships of the target array, they too received a thorough cleaning before they were boarded. For the tests the Navy perfected eight drones, used four during Test Able, six during Test Baker. The boats were converted LCVP's fitted with a mass of complex electrical gear to operate the starting, steering and sample- collecting mechanisms. Black stripes on a gaudy yellow base aided recognition by the conning aircraft.

William L. Laurence, center, eminent scientific writer of the New York Times, discusses the tests with Dr. Ralph A. Sawyer, left, Technical Director, and Colonel William Westlake, Deputy Public Information Officer, aboard the press ship "Appalachian." Mr. Laurence was the only correspondent to witness the first bomb test, in New Mexico; and he had the unique distinction of riding in the bomber that carried out the Nagasaki mission. Dr. Sawyer was responsible for all scientific instrumentation at Bikini,

A PBM plane of the Bikini-Kwajalein shuttle service unloads its cargo of mail into a launch from the AVP "Orca," seaplane tender that presided over the seadrome west of Bikini Island.

Following Test Able, one of the goats which had been exposed to the effects of the bomb is checked for radioactivity with a Geiger counter. For Test Able 176 goats were used. Some were coated with protective salves, some had portions of their hides shaved to expose parts that would best approximate human skin. No goats were used in Test Baker.

Surrourded by collecting bags, bottles, knapsacks, and other paraphernalia cherished by naturalists, Dr. Joseph P. E. Morrison, Assistant Curator of Mollusks at the U. S. National Museum, examines a seafaring bird caught at Bikini. Dr. Morrison became a familiar figure along the reefs and beaches of the Atoll. His unusual pistol, which had four interchangeable barrels of different sizes, attracted particular attention. Whatever the size or range of the bird he was gunning for, the right caliber was quickly available. Dr. Morrison was in charge of collection and examination of birds, land animals, mollusks, crustaceans.

In the radiation measurement section of the Instrumentation Laboratory on the AG-76 "Avery Island," Mr. A. H. Waite, Jr., checks the timing of an automatic pen- and-ink recording device. Recorders like this were used on support ships, several miles off Bikini, to make permanent records of data automatically gathered by instruments on the hot target ships within the Lagoon. Many of the Geiger counters on the target vessels were used in this way: they were equipped with radio transmitters which automatically broadcast the counter readings to these remotely-located recorders. Such continuous records were available for immediate use, or for more detailed analysis at a later time.

Aboard the APA-67 "Burleson" an officer from the Naval Medical Research Institute examines samples for radioactivity. With far less modern apparatus the Curies in the 1890's tested innumerable samples in their painstaking search

for the elements responsible for the newly discovered phenomenon, radioactivity.

In a caisson slung at a predetermined depth below this LSM- 60 is the atomic bomb used in Test Baker, which occurred at 0835 on the morning of July 25 by the Bikini calendar (July 24 in New York). Test Baker was the under water shot, designed to determine the effects of an underwater atomic bomb explosion upon ships, particularly ship hulls. Use of a surface vessel from which to suspend the bomb made possible a detonation at exactly the predetermined depth and at the exact center of the target array; all errors in positioning the bomb were avoided. Shown here is the antenna used to receive the radio signal which detonated the bomb. The midship hoist used for lowering the bomb caisson is also shown.

Scientist being checked into the well-guarded timing laboratory aboard the AV-17 "Cumberland Sound."

Dr. Marshall G. Holloway, Head of the Los Alamos Laboratory group at Bikini, throws the final electronic control switch on apparatus which a few seconds later detonated the Test Baker bomb. Signals controlled from this panel started automatic cameras and instruments a few seconds prior to the detonation.

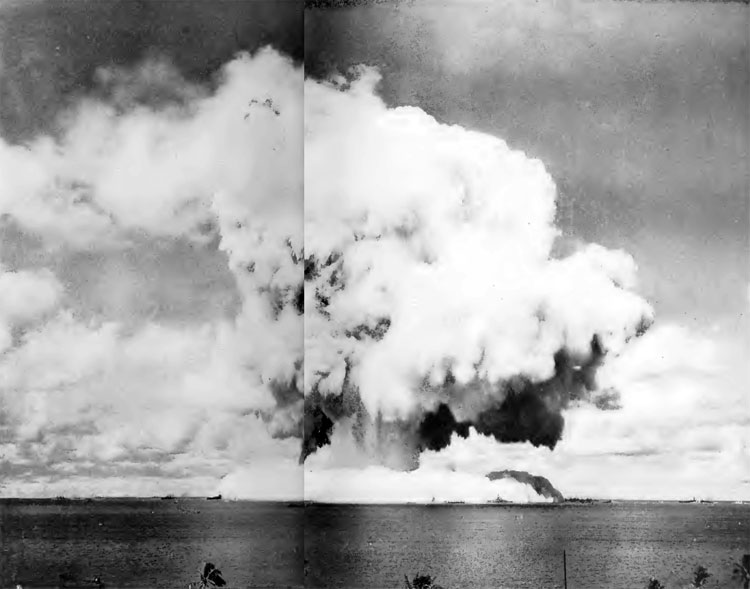

The Baker Day explosion burst through the calm, blue water of deserted Bikini Lagoon at 0835 on July 25, Bikini local time and date. Wind was from the south, and of low velocity; cloud coverage was very slight. Evacuation of the support fleet and of all personnel from the Lagoon was well underway by dusk of the preceding day; it was completed when the last remaining technicians quitted the Lagoon nearly two hours before the 0835 "Mike Hour." During the hour before the detonation shipboard observers selected vantage points on the uppermost decks.

High altitude view, Baker Test. This almost perfect birdseye view of the Baker burst was taken from directly overhead by a drone photographic airplane arriving exactly on schedule. To aid discussion of pictures like this, Task Force scientists developed their own terminology. In this photograph the rough central portion, or "cauliflower", is still in an early stage. Water which lay motionless a second before is now arising toward the camera with the speed of a bullet, spreading slightly as it rises. The surrounding white disc-shaped area, concentric with the cauliflower, is called the "fillet." It denotes the spread of the extremely intense pressure wave.

These photographs of the Baker Test, subject matter aside, are clear evidence of the accurate timing achieved in the second bomb test. By radio control an Army Air Forces B-17 drone plane has been brought to just the right position above the bomb detonation point, exactly at the instant of detonation. Other radio-controlled apparatus has activated the cameras that made these photographs. All such controls were synchronized with the signals detonating the bomb itself. Two stages in the development of the cauliflower are shown. The shock wave and fillet continue to expand, the cauliflower grows, the condensation cloud begins to assume its roughly spherical shape. Shadows cast by low-lying natural clouds form blotches on the explosion cloud below. Size of the target ships (right, above) indicates the height at which these pictures were taken and gives some conception of the magnitude of the burst.

Condensation cloud, Test baker. Dwarfinq the ships silhouetted against it, the roughly spherical region contains over one cubic mile of fog.

Oblique view of the condensation cloud and water mass rising up at the center. The Evaluation Board commented on Test Baker as follows: "The explosion was of predicted violence and is estimated to have been at least as destructive as 20,000 tons of TNT. To a degree which the Board finds remarkable, the visible phenomena of explosion followed the predictions made by civilian and service phenomenologists attached to Joint Task Force One. The blast was followed by an opaque cloud which enveloped half of the target array."

In this striking view of the Baker Day test the condensation cloud has disappeared near the surface of the Lagoon, revealing the target array and the up surging column of ten million tons of water. As if resentful of its imprisonment under water the bomb hurled this column of water, fully 2,200 feet in diameter, 6,000 feet into the air. The column is moving upward with such incredible speed that its remarkable mottled appearance is caught only on short-exposure photographs such as this. The condensation cloud now covers an area of approximately ten square miles. The dark hole on the right of the column marks the location of the battleship "Arkansas" which sank within a matter of seconds after the burst.

Shown at about the top of its rise, the millions of tons of water thrown up by the Baker bomb break through the enveloping condensation cloud before descending upon ships of the target array one mile below. Explosion of the bomb beneath the surface of the Lagoon subjected the surrounding water to many unprecedented effects, including intense neutron bombardment. This produced artificial radioactivity, particularly in the sodium, iodine, bromine, and potassium content of the water. Therefore most of the water in the column was dangerously radioactive. The bomb produced an amount of radioactivity estimated to have been the equivalent of many hundred tons of radium.

When this photograph was made the column of water had just reached the top of its rapid climb. Its surface has been replaced by individual jets or spurs each one of which is approximately the size of a large ship. In another moment the huge column begins its ominous descent. The condensation cloud is still present. In Test Baker the air blast wave was far less intense than it had been in Test Able. There was little optical radiation of any significance. Due to absorption of neutrons and gamma rays by the water of the Lagoon, the first flash of nuclear radiation had very little immediate effect on the target ships.

Taken a few instants after the picture on the preceding page, this photograph shows the last vestiges of the condensation cloud still encircling the water column. Invisible to the camera s eye, the complex instrument array is recording many statistics concerning this lofty column. Positive conclusions to affect ship design were to come later. On September 7, 1946, the significant announcement was made that construction on the 45,000-ton battleship "Kentucky," 70 per cent completed, and on the 27,000-ton battle cruiser "Hawaii," 85 per cent completed, would be curtailed until January 1947 pending design changes based on Operation Crossroads as well as on lessons learned during the war. And even more radical changes may be expected in the future.

A drone plane flying directly overhead just as the Baker bomb water column cached its greatest height recorded this interesting view of the cauliflower. Appearance of the condensation cloud suggests that this picture was made but a few instants after the view on the preceding page.

This oblique shot of the Baker burst again emphasizes the height of the cauliflower, size of which should be compared with the single ship of the target array visible just inside the expanding shock waves.

Shown here is the Baker burst water column starting its descent back into the Lagoon. Pulled now only by gravity, a puny force compared with that produced by the bomb, the water drops relatively slowly. Thundered back into the Lagoon from its mile-high vantage point, the millions of tons of water form colossal waves and an expanding cloud of spray and water plunging outward from the base of the column. Within a few minutes this engulfing mass, called by oceanographers the "base surge”, has shrouded approximately half the target array.

Oblique view, Baker Test. As is well known to photographers, use of yellow, orange, or red filters cuts down the amount of blue and ultraviolet light reaching the film, thus cutting out haze and leaving a dark background of sea and sky. Such filters were put to especially good use at Bikini, and are in large part responsible for the excellent contrast obtained, particularly in photographs taken from the air. A few Polaroid filters were used also. Some of the high-contrast photographs shown here actually provide greater contrast than was available to the naked eye.

Vertical view of Baker burst.

Somewhere beneath this free-shaped watery pile lies the battleship "Arkansas," which was the nearest to the center of impact when the Baker bomb was detonated. "Arkansas" and three other smaller ships sank almost at once. The aircraft carrier "Saratoga," also close to the bomb, sank seven and one-half hours later. The big battleship "Nagato" emerged from the Baker Test with a five degree list, remained in that condition for four days, sank in the middle of the night. Comparing the two tests, the Evaluation Board observed that ships remaining afloat within the damage area appeared to have been much more seriously damaged by the aerial explosion than by the underwater explosion. Damage to ships in the first test might have been far greater had the bomb exploded directly over the target ship "Nevada." No ship within a mile of either burst could have escaped without some damage to itself and serious injury to a large number of its crew.

These photographs re-emphasize the great scale of the Baker burst. They convey an impression that was the commonly-shared experience of on-the-spot observers—the difficulty mentally of taking in the spectacle before them. Note particularly, the row of destroyers lying in a sunny patch of sea not yet encompassed by the advancing cloud of water and spray. They are like minnows about to be engulfed by Niagara. Lost in comparison with the towering clouds of spray spreading out from the top of the cloud, some of these ships are shortly to be immersed in the wall of foam coming along the Lagoon s surface from the base of the column.

Base surge, Lagoon level. The wall of spray and steam at the base of the column rushes precipitately out from the center, drenching the target ships with its thick poisonous wetness. At the left all but the bow of the battleship "New York" has been overrun by the cloud. In the center and at the right, respectively, the "Salt Lake City" and "Nevada" have only seconds to wait. Small wonder that over 90 per cent of the target vessel array was affected by the deadly radioactivity. Although the amount of damage done to hulls was not very different from predicted damage, the extent of radiological hazards went beyond what had been expected. Lessons in radiological safety formed an important result of Operation Crossroads.

Second base-surge forms inside first.

The cauliflower in this stage is rapidly approaching the appearance of a mere cabbage. The height of the base-surge is easily estimated by comparison with the "Salt Lake City" just at the edge of it. Near the "Salt Lake City" clumps of spray and white marks in the water are splashes made, presumably, by portions of the LSM-60 falling back into the Lagoon after a spectacular flight into the air. Unlike Test Able, the Baker bomb was not a "self-cleansing" shot. Radioactivity in the Lagoon persisted for weeks. It produced in the salt water lines and condensers of various returning Crossroads vessels a radioactive residue which was disclosed by a precautionary check made when the ships arrived at the West Coast. During the entire conduct of Operation Crossroads no casualties from radioactivity occurred, testifying to the extreme precautions taken.

As the base surge completes its lateral spreading, the cloud, drained by gravity of its water content, floats off with the wind. During the first hour her northward progress was easily watched by observers on surface vessels; the cloud retained a slight orange t'nt, and appeared somewhat larger than other clouds. By the end of the second hour she was practically indistinguishable from the countless clouds dotting the horizon; and all attention reverted to the destruction in the Lagoon. Specially-equipped planes were able to follow the cloud some time longer.

Wave Motion, Test Baker. These waves, shown reaching the beach at Bikini, are the dwindled remnants of waves which at 1000 feet from the explosion center were 80 to 100 feet in height. Largest waves reaching Bikini beach were about seven feet high. Although they did not pass over the Island they flooded the Island roadway and several other areas. No material damage occurred, however.

Dr. S. K. Green, formerly a major in the Army, instrumentation expert of the Army Ground Group, studies a telemetered recording made on an Esterline-Angus recorder on the AG 76 "Avery Island." "Telemetering" is the process in which automatically-made readings of instruments are radioed to a point some distance away and are there recorded.

COUNTERS, TIDES, AND WINDS. Two radiological monitors of the Task Force work their way into a contaminated portion of the Lagoon using a Geiger counter to take readings of radioactivity in the water.

A United States Navy fireboat washes down the decks of the battleship "New York" with sea water shortly after the Baker Test. This procedure was carried out with many of the target ships prior to sending inspection parties aboard. High pressure firehose streams washed much radioactive material from the decks, making the initial reboardings after the test far less dangerous than they would otherwise have been. During the Test Baker explosion great quantities of radioactive water were thrown upon the ships, either by the great column tossed up or by the enormous waves. This innocent-appearing but radioactive water was such a hazard even after four days, that it was still unsafe for inspection parties to spend any useful length of time at the center of the target area.

End of the "Sara." As the cloud lifted following the Baker blast, and the target array once more became visible, there was no question but that the gallant aircraft carrier "Saratoga," oldest U. S. aircraft carrier afloat, was seriously damaged. All moored planes and material on her deck had been swept into the Lagoon. Much of her superstructure was gone or extensively damaged. The very distinctive stack (upper) was completely gone. When ships of the supporting fleet began re-entering the Lagoon after the test, and it was certain that "Saratoga" was on her way down, Admiral Blandy ordered tugs to attempt to secure lines to the carrier and tow her to Enyu Island for beaching. This proved impossible since both "Saratoga" and the water surrounding her were too "hot" to permit safe approach.

The sinking of Old "Sara" was watched with mixed emotions by members of the Task Force, many of whom had served on her during her fighting days.

This composite photograph roughly compares the height of the Baker Day cloud with the height of New York's greatest skyscraper. An exact comparison to scale would, if anything, be even more extreme than this; the great cloud rose to approximately 6000 ft., and the Empire State Building is only 1250 ft. in height. The greatest cauliflower cloud would overshadow a considerable portion of central Manhattan. It requires little study to appreciate that one atomic bomb is capable of producing catastrophic destruction.

FULL FATHOM FIVE. Underwater photography was used at Bikini to record damage to hulls and superstructures of sunken vessels. This work was especially significant after Test Baker, in which a particularly large fraction of the interesting mechanical damage occurred on ships which sank. The diver shown is preparing to descend from the specially equipped LCM used in this work. He wears a simple face mask and a quick-release type of lead-weighted belt.

Underwater photography techniques experimented with at Bikini were not particularly hazardous, although voracious barracuda, sharks, and eels occasionally turned up to see what was going on. Fortunately these fish will avoid

a man who moves about underwater, especially if there is a column of air bubbles escaping from helmet or face mask. Some sharks 12 feet long were seen, but they kept their distance. Smaller fish, less reticent, ventured closer, formed a colorful array of onlookers as the photographic work proceeded.

Pictures like this were made by photographers working far beneath the surface of the Bikini Lagoon. Artificial illumination synchronized with light-meter readings aided obtaining good exposures. The extremely clear water of the Lagoon also favored this subsurface work. After Test Baker the bottom of the Lagoon was found to be covered with many feet of fine silt, pulverized coral resulting from the bomb's explosive force released beneath the water. Divers sank into this silt up to their shoulders. Jagged coral heads and radioactivity added to the difficulties.

Off Enyu Channel sailors on a San Francisco-bound Task Force ship take a final look back at the scene of the two atomic bomb tests. Many of the 42,000 members of the Task Force left Bikini soon after Test Baker. Others remained there to do necessary post-test "mopping up". For the scientists and service personnel of

the technical groups, however, possibly the most important part of the Operation still lay ahead— the important work of consolidating results. Wise was the scientist who once laid that he never knew what the results of an experiment were until he had written them down. By mid-October most of this work had been accomplished.

The "Burleson," arriving home from Bikini, symbolizes a cogent truth: The problems with which the atomic bomb confronts us do not, after an Operation Crossroads, remain behind, imprisoned with the coral bounds of a remote Pacific

atoll. At Bikini ships were sent to the bottom, the problems were not. As examples of man's scientific skill and cooperativeness the atomic bomb, and Operation Crossroads, are unrivalled. To those who direct man's humanitarian destiny the challenge is clear.